Atheists are champions of science and reason who have carefully and honestly examined the evidence for God’s existence and found this evidence sorely lacking. Now that they’ve thoroughly debunked belief in God, they find it very easy to demonstrate how stupid, intolerant and ignorant Christians are for believing in “sky daddy”. Christianity is unfounded and outdated. Science, reason, and logic contradict religious faith, and those with religious affiliations are not only misinformed but are also adversaries to scientific and rational thinking. Religious beliefs are the result of inadequate scientific understanding, often stemming from early indoctrination. In the end, faith in God is a product of blind faith and emotional attachment, lacking rational justification.

This mode of thinking is not only oversimplified but also arguably arrogant. It dismisses the complex, nuanced reasons people may have for their faith and overlooks the possibility of intelligent, reasoned belief behind religious conviction. This dismissive attitude was starkly evident in a personal encounter I had. In a casual conversation about weekend plans, my mention of attending church was met with a startling response: “Wait, you believe in God? I have lost all respect for you!” This person abruptly ended the conversation, showing a swift and uncompromising judgement based solely on my Christian worldview. In another conversation about my faith, I shared that my journey to Christianity began with seeking satisfactory and compelling answers to the big questions of life — origin, meaning, morality and destiny. In this quest, I found myself drawn to Christianity. It’s not that I claim to have all the answers now, but rather, I believe that the answers are found in God. However, I was hit with a dismissive response — “Rubbish! You can’t be a truth seeker and Christian! I mean, do you genuinely accept the idea that Adam and Eve were the first people, living just six thousand years ago?” I began explaining that to properly interpret Genesis requires understanding it within the ancient Hebrew cognitive context. This perspective doesn’t imply Adam and Eve as the literal first humans, but rather the first symbolic archetypes representing humanity before God. However, in response, I was called a “deluded child” and that was the end of the conversation.

On another occasion, I read up an online atheist forum, hoping to get a deeper understanding of the arguments presented against Christianity. To some degree, this was helpful, but I also encountered numerous straw man arguments and dismissive insults. One post read, “Fuck Christianity (and all Christians). All Christians do is hinder the world with their irrational, oppressive philosophy.” The thousands of comments echoed this sentiment, uniformly disparaging Christians in a manner that underscored this sentiment. Phrases like, “We all know Abrahamic religions are a cancer… No one is going to change my mind”, were common. It was more than just disagreement. It was resentment.

Now these experiences showed me something — just like many of the religious, atheists’ can also often be entrenched in their stances, unwavering in their rejection of any evidence supporting the existence of God. They typically maintain that there is absolutely no credible evidence supporting the existence of God. They are, in a way, much like the religious people they criticise. I came to see a community of people who will reject any evidence for God, no matter what it is. This approach reminded me of subtle cult tactics, where there’s a lure of intellectual elitism and a promise of belonging to a “smarter” group. The underlying message to those on the fence is, “Hey, do you aspire to be part of an intellectually superior community? Then be an atheist. If you’re unsure, bear in mind that the religious are closed-minded, anti-scientific, uneducated, irrational, ignorant and hateful. Align with us instead, the group that is committed to science and rational thought.” This allure of being intellectually and morally superior appears to be a calculated method to draw in and keep members, reinforcing the group’s collective stance while subtly discrediting differing perspectives. This tactic, it seems, is less about promoting open-minded exploration and more about inappropriately hijacking the banner of rationalism, science, and open mindedness over a particular ideology. In reality, I believe that atheism contradicts the very tenets it claims to uphold.

For instance, let’s talk about being open-minded: Richard Dawkins was once posed a question: if God did exist, what kind of evidence would be convincing enough for him to believe in God’s existence? Dawkins admitted that even if he heard God’s voice, he would likely dismiss it as a hallucination. Furthermore, he stated that if God were to write a message in the stars, he would attribute such a phenomenon to the work of advanced aliens rather than anything divine.

This perspective is not unique to Dawkins. Peter Atkins, an esteemed Oxford chemist and another vocal atheist, was similarly queried about what evidence could potentially sway his belief that there is no God. The interviewer challenged Atkins, suggesting that some might view him as so staunchly committed to atheism that he would refuse to acknowledge any evidence supporting a Creator. The question posed was: what kind of scientific or physical evidence could lead him to reconsider his stance on the existence of a mind behind the universe?

Atkins’ response was strikingly similar to that of Dawkins. He quipped that even if the stars aligned to spell out a personal message from God, such as “Peter, it’s God, please believe in Me,” he would dismiss it as a sign of madness. He went further to say that even if he stood before the foot of a cross at Jesus’ crucifixion, and then later saw the resurrection before his very eyes, he would put it down to hallucination.

This stance raises a critical question about the nature of their supposed evidence-based views. If Atkins, like Dawkins, is prepared to reject any conceivable evidence of a divine presence, can their views still be considered based on evidence? Or are they inherently committed to atheism, regardless of potential evidence?

This commitment to atheism as an a priori belief system, one that is unfalsifiable and immune to any form of evidence suggesting a divine/transcendent intelligence, presents a significant challenge. Engaging in reasoned debate becomes difficult when someone’s stance is so firmly entrenched that it excludes the possibility of any evidence contrary to what they want to hear. Such a position, resolutely rejecting any notion of a mind behind the universe and labelling any suggestive evidence as madness or misinterpretation, suggests a level of commitment to atheism that goes beyond a simple lack of belief in a deity. It implies a predetermined conclusion that is unshakeable. Ironically, the same people who assure us that they’re committed to going wherever the evidence points, are really just reinterpreting or explaining away evidence that points in a direction they don’t like.

While it’s crucial to avoid generalising all atheists based on well-known figures such as Dawkins and Atkins, I have observed that among the more vocal segments of the atheist community, there tends to be a similar approach. It’s important to recognise, however, that this may not represent the views of the broader atheist population. The takeaway from all of this isn’t that these atheists simply follow the evidence, the takeaway is that pretty much any evidence can be reinterpreted and explained away by people who are committed to an unfalsifiable position. Atheists aren’t educating the rest of the world following the evidence. The leaders are giving a tutorial on how to reinterpret and explain away evidence that they don’t like, and on how to psychologically condition people by making them think that they’re part of some elite group.

To clarify, my intention is not to dismiss the thoughtful and valid reasons that philosophical atheists may have for their belief in a godless universe. That’s a distinct and worthy discussion in itself. The issue I’m addressing is the emerging trend among some atheists to assert intellectual dominance and to adopt an almost cult-like attitude. This involves positioning atheism as the ultimate proprietor of rational thought, science, and reason, to the extent of labelling Christianity as fundamentally opposed to intellectual pursuits, akin to saying “if you’re a Christian, then you’re an enemy of justice, science…” Such a stance not only over simplifies the complex landscape of Christian thought, but also undermines the rich, intellectual tradition present within Christianity. It has reached a point where some atheists are so entrenched in their views that they refuse to even consider a meaningful dialogue with a theist. And on the occasions when such discussions do occur, they often devolve into mocking and dismissive commentary, lacking the respect and open-mindedness essential for constructive discourse. Christians can be guilty of this approach too, and I’ve seen that first hand. But the pendulum has swung, and I’m worried how this will evolve in the near future — where respectful dialogues will be overthrown with resentful and dismissive debates.

I can give 101 rational reasons for my belief in the Judeo-Christian God — employing logic, philosophy, science, and history. My faith (that is, my trust in God), is evidence based. I can go further to give reasons why I believe that philosophical atheism is intellectually self-defeating. It’s empirical evidence and the tenets of scientific method that have led me to reject naturalism and philosophical atheism. Now, I admit that I still have many questions about my own worldview – God is enigmatic; I do not claim to have a complete understanding of Him. At the same time, I am able to engage and have discussion about critical topics such as the problem of suffering in relation to the concept of God, or the interplay between evolution and theism. I am more than happy to explain my views, but engaging with those who have firmly closed their minds to my ideas would be a waste of time. We all need to carefully select our dialogues, discerning whether the person asking questions genuinely seeks understanding and reflection, or if their motive is just to dismiss.

To the adamant atheist (and equally to the rigid theist), it’s crucial to recognise that in the quest for truth, the sincerity of your intentions is primary to the substance of your arguments. We must all examine our motives and listen attentively to the language we employ in debates, discussions, or when advocating for particular ideas and beliefs. All of us are capable of selectively choosing information that aligns with our preferences, or even subconsciously manipulating evidence to fit our worldview. Consequently, while the merit of an argument is based on its content, we should also question the sincerity and openness underpinning it. We should all be able to entertain alternative views without necessarily accepting them, respecting that there might be complex and thoughtful explanations that we have overlooked.

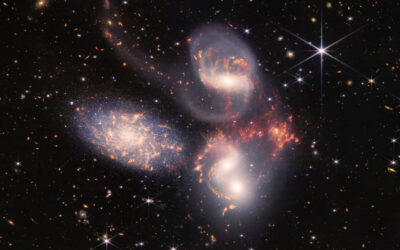

It’s interesting that many atheists, seemingly without scientific evidence, are open to the possibility of other dimensions, yet they mock the concept of a spiritual domain. They might contemplate the universe as being eternal, but would immediately dismiss the notion of an eternal God. They might entertain the possibility of intelligent life elsewhere in the cosmos, yet the theory of intelligent design on Earth is frequently dismissed as ridiculous. Intriguingly, when the conversation turns to the origin of life on our planet, the idea of an intelligent source is sometimes accepted — but only if that source is extraterrestrial. It seems there’s a willingness to consider any possibility, as long as it steers clear of the idea of a God. Anything but…

In our pursuit of truth, whether we align with faith, scepticism, or somewhere in between, what remains crucial is our capacity for curiosity and a willingness to engage in generous argumentation with those holding divergent views. Just as scientists approach the unknown with a hypothesis to be rigorously tested and debated, so too should we approach our discussions of belief and scepticism. This method, the cornerstone of scientific inquiry, should also guide our conversations about faith and disbelief.