The Big Bang

Prior to the early 20th century, most scientists thought that the universe had always existed. An eternal universe seemed to strike a chord with the scientific community because the theory has a certain elegance, simplicity and completeness to it. It’s obvious why – if the universe has existed for eternity, then there was no need to explain how it was created, when it was created, why it was created, or, dare I say, Who created it. Atheistic scientists were particularly proud that they had developed a theory of the universe that no longer relied on invoking God.

But now that’s under threat. One of the most remarkable discoveries of the 20th century is that the universe had a beginning. That was a strange idea under a naturalistic cosmology because, given the naturalistic view that ‘nature’ exists on its own and is all that is, we wouldn’t expect the universe to have a beginning. All initiating causes for the universe would have to lie within the universe, which doesn’t really make sense.

This view that the universe had a ‘start’ – an origin, started to be reconsidered as a serious theory when one astronomer noticed something odd. Edwin Hubble observed that the light coming from galaxies had a colour hue according to the distance they were from the earth, with further galaxies taking on a slightly redder tone. He proposed that this ‘redshift’ was due to the speed at which these galaxies were receding away from earth, similar to the audible Doppler effect that we hear when an ambulance speeds past. Just as the pitch of the ambulance’s siren drops as it recedes from us, in the same way, further galaxies appear slightly redder as they move away from us in proportion to their relative speed. Hubble decided to plot the recessional velocity and distance from the earth of the different galaxies and discovered a precise linear relationship between recessional velocity and distance. In other words, the rate at which other galaxies retreat from ours correlates directly with their distance from us – just as if the universe were undergoing a spherical expansion like a balloon being blown up in all directions from a singular point of origin.

Hubble’s discovery of an expanding universe was fraught with theoretical and philosophical significance. It meant that at any time in the finite past the galaxies would have been closer together than they are today, but as we wind the clock back, not only would the galaxies have been closer and closer together, but eventually all matter and energy would have converged, bunching up on each other at some moment in the past. The moment where the galaxies converge marks the beginning of the expansion of the universe and, arguably, the beginning of the universe. In any case, Hubble’s discovery implied an expanding universe in the forward direction of time and a finite universe with a definite beginning in the distant past. His discovery implied that the universe was expanding and had a beginning.

The evidence of galactic redshift, suggesting an expanding universe, was startling. But it became even more revolutionary when conjoined with Albert Einstein’s new theory of gravity known as ‘general relativity’. Eventually, the synthesis of Einstein’s theory of gravity with the evidence for an expanding universe from observational astronomy came to be known as the Big Bang Theory.

The Big Bang Theory was proposed by a Belgian priest and physicist named Georges Lemaître. When Lemaître integrated the observational evidence of redshift into a cosmological model based upon his solutions to Einstein’s field equations, his model implied that space itself was expanding. That, in turn, implied that the universe would have been much smaller in the past. More startlingly, it also implied, in the words of physicist Stephen Hawking, that “at some time in the past… the distance between neighbouring galaxies must have been zero.” Thus, Lemaitre both solved the field equations and used the redshift evidence (anticipating much of Hubble’s later work) to develop a comprehensive cosmological model.

So, to summarise so far, Albert Einstein found that his mathematical equations described a universe which was either blowing up like a balloon or else collapsing in upon itself. During the 1920s George Lemaître used Einstein’s equations to create a model of an expanding universe. In 1929 the American astronomer Edwin Hubble made a discovery that verified Lemaitre’s theory, and this theory is commonly known as The Big Bang.

The Big Bang is the story of an expanding universe, and so as you trace the expansion of the universe back in time, everything gets closer and closer together. Like a balloon that keeps shrinking and shrinking, eventually the distance between any two points on the balloon’s surface shrinks to ‘zero’. At that point, the universe has reached the boundary of space and time. With the Big Bang, the realm of spacetime came into existence, and with it all matter and energy. If this Bang never banged there wouldn’t just be no matter and energy but the very dimensions of space and time wouldn’t have come into existence. There was no time ‘before’ the Big Bang as the dawn of spacetime was the introduction of time.

Therefore, although the Big Bang model does not give a causal explanation to the universe, it does give us a label saying that there was a definite beginning. The universe – the system of time, space, matter and energy – has not eternally existed but began to exist some finite time ago.

The Big Bang Theory began to shift the thoughts of many scientists. This new understanding of our origins sent shockwaves throughout the hallowed halls of departments of science, philosophy and theology. The jarring revelation to many scientists was that an absolute beginning to our universe pointed to something outside of physical reality that started everything, naturally leading to the revival of the God hypothesis. Allan Sandage, widely respected as one of the greatest observational astronomers of the twentieth century, shocked many of his colleagues by announcing a recent religious conviction, explaining how the scientific evidence of a “creation event” had contributed to a profound change to his worldview. Gravely he stated, “here is evidence for what can only be described as a supernatural event. There is no way that this could have been predicted within the realm of physics as we know it.” In the mind of Sandage, something beyond the strictly material must have played a role in bringing the universe into existence. Sandage continued:

“I find it quite improbable that such order came out of chaos. There has to be some organising principle. God to me is a mystery but is the explanation for the miracle of existence, why there is something rather than nothing.”

The theological implications of the universe having a beginning were immediately recognised and resisted by many. For instance, Physicist Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington OM FRS responded: “Philosophically the notion of a beginning of the present order is repugnant to me. I should like to find a genuine loophole. I simply do not believe the present order of things started off with a bang…it leaves me cold.” In fact, the term Big Bang was coined by physicist Fred Hoyle to express his derision at the idea of a beginning. Surprisingly, the term stuck. Hoyle acknowledged that his resistance was due to the theory’s religious implications.

Singularity theorems

Since the late 1960s further developments in theoretical physics have supplied additional support for the idea that the universe as well as space and time – or spacetime – had a beginning. Stephen Hawking played a central role in making these theoretical advances.

During his PhD research, Stephen Hawking encountered the work of physicist Roger Penrose. Penrose was working on the physics of black holes – locations in space where matter is so densely concentrated that even light cannot escape the gravitational pull of the mass. According to general relativity, the dense concentration of matter in a black hole will warp or bend the fabric of spacetime, creating a tightly curved, self-enclosed region of space. Such a dense concentration of matter makes a kind of gravitational trap that prevents anything on the inside of the tightly curved space from getting out – even light. Thus, the name “black hole.”

Now, Hawking realised that Penrose’s work on black holes had implications for understanding the origin of the universe. He realised that at every point in the past the mass of the universe would have been more densely concentrated. That meant that space would have been more tightly curved at every successive point farther and farther back in time. In his mind’s eye, as he extrapolated backwards in time, he saw that at some point the curvature of the universe would reach a limit – that is, it would attain an infinitely tight spatial curvature corresponding to a zero spatial volume. This is called a “singularity,” where the known laws of physics would break down and from which the universe would have begun its expansion. Hawking showed that, given such a finite termination point for light and time in the past, “there will be a physical singularity… where the density and hence the curvature (of the universe) are infinite.”

Hawking and Penrose teamed up and developed additional mathematical arguments for a spacetime singularity. Then, in 1973, Hawking developed his case further with physicist George Ellis. These three physicists produced a series of scientific publications that spelt out the implications of Einstein’s theory of general relativity for the origin of space and time. Their solutions to Einstein’s field equation implied a singularity at the beginning of the universe where the density of matter and the curvature of space would approach infinity.

So, as far as we can tell, the universe began from a singularity in which the gravitational field would have been infinitely strong and the curvature of space infinitely tight. Oddly, however, an infinitely tightly curved space corresponds to a radius of curvature of zero units in length and thus to zero spatial volume. This implies a fixed beginning to the universe, as Hawking and Ellis wrote, “that there is a singularity in the past that constitutes, in some sense, a beginning of the universe.” In 1978, the British physicist Paul Davies described the implications of the singularity theorems with great clarity:

“If we extrapolate this prediction to its extreme, we reach a point when all distances in the universe have shrunk to zero. An initial cosmological singularity, therefore, forms a past temporal extremity to the universe. We cannot continue physical reasoning, or even the concept of spacetime, through such an extremity. For this reason, most cosmologists think of the initial singularity as the beginning of the universe. In this view, the Big Bang represents the creation event; the creation not only of all the matter and energy in the universe but also of spacetime itself.”

There’s no reason or evidence to believe that matter nor energy can exist in the absence of space and time. Thus, Hawking, Ellis, and Penrose’s singularity proofs implied that a material universe of infinite density began to exist some finite time ago starting from nothing – or at least from nothing spatial, temporal, material, or physical. That seemed a bit odd because nothingness can’t be the explanation of anything, since nothing by definition is hard to imagine. We can imagine empty space, but empty space is something, not nothing. Nothing is the absence of anything whatsoever, even space itself. Nothingness is literally no properties at all since there isn’t anything physical to have any properties.

Taken at face value, the philosophical implications of a cosmological singularity are staggering, since it poses an acute challenge to any materialistic theory of the origin of the universe. A singularity implies that not only space and time but also matter and energy first arose at the beginning of the universe, before which no such entities would have existed that could have caused the universe (of matter and energy) to originate. What’s more, insofar as the spacetime singularity marks the point of origin of the universe from nothing physical, cosmological models based on solutions to the field equations of general relativity seem strangely reminiscent of what theologians long described in doctrinal terms as creatio ex nihilo – “creation of out of nothing” – nothing physical, that is.

The limitations of singularity theorems

General relativity stands as one of the best-confirmed theories of modern physics. Questions about the applicability of the theory of general relativity arise, however, from extremely small subatomic and quantum-level phenomena. In the subatomic realm, strange phenomena can concur, such as light or electrons acting like both waves and particles at the same time. Nondeterministic fluctuations in energy can occur at that scale as well. Since general relativity does not describe such effects, many physicists have proposed the need for a quantum theory of gravity, though no such theory has yet been definitively established.

The inability of general relativity to describe gravitational phenomena on an extremely small subatomic scale has led to questions about the applicability of the theory during the earliest history of the universe, the first fraction of a second after The Big Bang. Hawking, Penrose, and Ellis recognised this limitation in their proofs of the cosmological singularity. They acknowledged that general relativity only allowed them to extrapolate backwards with absolute confidence to a point in the past where the universe had a radius of curvature of somewhere between a trillionth of a centimetre and a billion trillion trillionth of a centimetre. Understandably, however, they regard a universe that tiny as effectively a spatial singularity. As they put it, “such a curvature would be so extreme that it might well count as a singularity.” So these singularity theorems did provide, for all practical purposes, a strong indicator of – or a pointer to – such a beginning.

Doubts from inflation cosmology

Unsurprisingly, many academics have attempted to overturn the conclusion of a beginning through the most creative of means. The first major attempt was by Fred Hoyle, physicist Thomas Gold, and mathematician Hermann Bondi, who constructed a “steady-state” model for an eternal universe. They acknowledged that the galaxies were receding from each other, but they circumvented the need for a beginning by proposing that matter was constantly being created between the galaxies. The new matter eventually coalesces into galaxies so that the density and other features of the universe never change. They believed that this process could have been occurring indefinitely into the past. Ultimately, their model was rejected in the 1960s because it predicted that galaxies of all ages should be observed throughout the universe, yet astronomers have only identified galaxies of middle age or older.

The next attempt to eliminate the beginning was introduced by Polish physicist Jaroslav Pachner, who suggested the oscillating-universe model. There have been several versions of this model, but in simple terms, the model postulates that the universe expands until it reaches a maximum size. Then it contracts due to gravity until it shrinks to a sufficiently small size that it, through some unknown mechanism, undergoes a cosmic bounce and then expands again. This cycle is said to repeat itself eternally. In the end, the oscillating model was rejected by most scientists due to the problem of entropy. Specifically, the entropy (disorder) of the universe increases continuously. Consequently, each cycle would end up lasting a longer period of time. Looking backward in time, earlier cycles would last for shorter and shorter periods until the period would reduce to zero, which is impossible.

Nevertheless, other developments in theoretical physics and cosmology soon challenged the standard Big Bang model and reinforced concerns about the applicability of singularity theorems to the early universe. Later still, in an oddly unexpected reversal, these same developments eventually led theoretical physicists to discover that the universe must have had a beginning after all. Here is the story.

During the 1980s, the physicist Alan Guth, of MIT, Andrei Linde, of Stanford, and Paul Steinhardt, of Princeton, developed an alternative version of the Big Bang cosmology known as inflationary cosmology. Inflationary cosmology asserts that soon after the Big Bang, space experienced a short-lived but exponentially rapid expansion. This expansion was due to the negative gravitational pressure produced by a postulated “inflation field”- a field that physicists conceived as generating an outward pressure on space, causing the universe to expand.

As originally proposed by Alan Guth, inflation presupposed a beginning of the universe after which the space of the universe would rapidly expand for a brief period of time. Subsequently, however, other physicists proposed “eternal chaotic inflation” – models that envisioned not a beginning, but an infinite number of beginnings. These eternal inflation models grew in popularity among proponents of inflation, because many thought that the postulated “inflation field” would be subject to quantum fluctuations in the energy of the field. As a result, these fluctuations would necessarily produce causally disconnected regions of space – effectively, separate “bubble universes.”

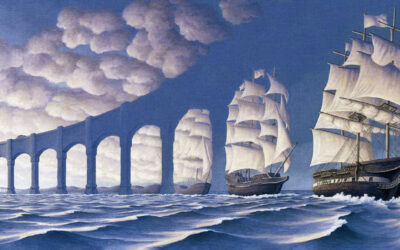

This diagram I found in a book gives you an idea of the two models.

According to current eternal chaotic inflation models, after an initial phase of expansion, a quantum fluctuation in the energy of the inflation field caused it to decay locally to produce our universe. The inflation field also continued to operate outside our local area to produce a wider expansion of space into which other universes were birthed as the inflation field decayed at other locations. Inflationary cosmologists envisioned inflation as having operated for an indefinitely long time in the past and continuing indefinitely into the future. They, therefore, anticipated that the wider inflation field will spawn an endless number of other universes as it decays in local pockets of an ever-growing volume of space.

Various eternal chaotic inflation models have now replaced Guth’s original model. Unlike the standard inflation model, these new models challenge the idea of a beginning – and of a cosmological singularity. The ‘eternal chaotic inflation’ employs the metaphor of an eternally existing multiverse and thus does not require a unique beginning or an ultimate end of the cosmos. Why? Because according to Linde’s theory, there has always been a yesterday and there will always be a tomorrow. Our universe grew out of a quantum fluctuation in some pre-existing region of the space-time continuum. Linde argues that “Each particular part of the [multiverse] may stem from a singularity somewhere in the past and it may end up in a singularity somewhere in the future.” Some parts may stop their expansion and contract, but inflation ends at different times in different places. There are always parts of the multiverse that are still inflating, with universes like ours eternally being produced.

Although the eternal chaotic inflation model prompted doubts about whether the universe did in fact have a beginning, it ultimately motivated another investigation in theoretical physics that led to a new even more compelling proof of the beginning – indeed, one that holds whether or not inflationary cosmology turns out to be correct.

In any case, by the early 1990s, many physicists had embraced eternal chaotic inflation as the best cosmological model for the universe. The popularity of the model led two physicists, Arvind Borde and Alexander der Vilenkin, to investigate what inflation implied about whether the universe had a beginning. They sought to investigate whether the inflation field could have been operating for an infinitely long time back in the past – that is, whether it could have been “past eternal”, as they phrased it. Within a decade, Borde, Vilenkin, and Alan Guth (one of the original proponents of inflation), had come to a startling conclusion: the universe must have had a beginning, even if inflationary cosmology is correct.

BGV theorem

In 2003, Borde, Guth, and Vilenkin developed a proof for a beginning of the universe that did not depend on using Einstein’s field equations of general relativity or on any energy condition. Instead, the Borde-Guth-Vilenkin (BGV) theorem is based solely on geometric arguments and Einstein’s theory of special relativity. Special relativity addresses the relationship between the speed of light and time. So, if Einstein’s gravity requires some modification, the BGV theorem conclusion will still hold. Consequently, the theorem applies to nearly all plausible and realistic cosmological models. It states that any universe that is on average expanding is “past incomplete.” In other words, if one follows any spacetime trajectory back in time, any expanding universe, including one expanding as a consequence of an “inflation field,” must have had a starting point to its expansion, indicating a beginning.

Borde, Guth, and Vilenkin have shown that all cosmological models in which expansion occurs – including inflation cosmology, multiverses, and the oscillating and cosmic egg models – are subject to the BGV theorem. Consequently, Vilenken argues that evidence for a beginning is now almost unavoidable. As he explains:

“With the proof now in place, cosmologists can no longer hide behind the possibility of a past-eternal universe. There is no escape, they have to face the problem of a cosmic beginning.”

The impossibility of an infinitely old universe

There’s also another reason to believe the universe had a beginning, this time, not predominantly from science but from another arena – philosophy.

One philosophical argument involves the impossibility of crossing an actual infinite number of events. If you started counting 1,2,3,…, then you could count forever and will never reach a time when an infinite amount of numbers had been counted. The series could increase forever (a potential infinity), but would always be finite (and thus could never be an actual infinity). Trying to count to infinity is like attempting to jump out of a pit with infinitely tall walls – walls that literally go forever without a top to them. No matter how far you counted, no meaningful progress would be made because there would always be an infinite number of items left to count.

Now, suppose we apply this to the universe. If we say the present moment is marked zero, and each moment in the past (such as yesterday -1, and the day before -2) is one point on the line to infinity. If the universe never had a beginning, the left side of the line has no end. Rather, it extends infinitely into the past. If the universe had no beginning, the number of events crossed to reach the present moment would actually be infinite. It would be like counting to zero from negative infinity. The issue with this is that it’s philosophically impossible to cross an infinite number of events into the past.

Perhaps these two illustrations will help explain:

Say you have an infinite number of balls, if I take 2 balls away, how many do you have left? Infinity. Does that make sense? Well, there should be two less than infinity, and if there is, then we should be able to count how many balls you have. But this is impossible because the infinite is just an idea and doesn’t exist in the real world. The concept of the actual infinite cannot be exported into the real world, because it leads to contradictions and doesn’t make sense.

Or imagine you are a soldier ready to fire a gun, but before you shoot you have to ask permission for the soldier behind you, but he has to do the same, and it goes on for infinity. Will you ever shoot? No. This highlights the absurdity of an infinite regress and this applies to causal events too. If it took infinite steps to get to where we are today, we’d never have gotten here. Therefore, there cannot be an infinite number of past events.

I am reminded of the German mathematician David Hilbert, who said: “The infinite is nowhere to be found in reality. It neither exists in nature nor provides a legitimate basis for rational thought… the role that remains for the infinite to play is solely that of an idea.” Although ‘infinity’ is sometimes needed to complete mathematics, it occurs nowhere in the physical universe, which therefore dismisses the idea of an infinitely existing universe.

Weighing up the evidence

So, did the universe begin? Not only does it make philosophical sense to believe it did, but we have multiple lines of scientific evidence to assume so:

Firstly, if we apply the second law of thermodynamics, the universe cannot be infinitely old. This law states that the amount of useful energy in the universe is irreversibly being used up. If the universe were infinitely old, it would have already used up all its useful energy. Since there are many pockets of useful energy (for example, the sun), the universe must be finite in duration. Therefore, there was a beginning, when the universe’s energy was put into it “from the outside.” If the universe had already existed throughout an actually infinite past, it would have reached an equilibrium state an infinite number of days ago, but it obviously has not done so.

Secondly, in the case of the Hawking-Penrose-Ellis singularity theorems, we have a strong indication that the universe began.

Finally, in the case of the BGV theorem, we have proof that the universe did have a beginning. The Border-Guth-Vilenkin theorem implies that time had a beginning. And since time and space are linked (not only in general relativity but in newer theories of quantum gravity), affirming a beginning of time would seem to imply a beginning to space as well, even if space began with a finite (nonzero) volume.

So there we have it. The Big Bang singularity model, along with BGV theorem and general relativity implies a creation event.

The weakness of naturalistic explanations

Science has done a great job explaining how the universe operates. What it has not done, however, is offer an adequate materialistic explanation for the origin of the universe. Why not? Well, actually it turns out to be pretty obvious why it can’t, as we shall see.

If we hold the naturalistic view that the cosmos is all that is, then nothing else exists beyond or separate from it that could act as its cause. This is why a cosmic beginning is so unexpected from a naturalistic point of view. If the universe began to exist, then that would imply that whatever properties we associate with the universe – space, matter, and energy as well as time – also began to exist. If matter came to exist then you can’t invoke matter as the cause of the material universe, you need something immaterial, which transcends matter. To say a materialistic process created the material world is to argue in a loop – it’s philosophical nonsense because its creation depends on its existence. To put it another way, it makes no sense to invoke a (1) naturalistic explanation for the (2) origin of nature, because the first point depends on the second.

The origin of the universe would seem to require – by the principle of sufficient reason – a cause. But since, according to naturalism, nothing exists except the natural world, then nothing else could have functioned as the cause of its coming into existence. The beginning of the universe raises a question that naturalists, almost by definition, cannot answer, namely, “What caused the whole of nature or the physical universe itself to come into existence?” For this reason, a causally adequate explanation for the beginning of the universe must be non-naturalistic.

The Hawking-Penrose-Singularity theorem amplifies this conclusion. If sometime in the finite past, either the curvature of space reached an infinite and/or the radius and spatial volume of the universe collapsed to zero units, then at that point there would be no space and no place for matter and energy to reside. Consequently, the possibility of materialistic explanations would also evaporate, since at that point neither material particles nor energy fields would exist. Indeed, since matter and energy cannot exist until space (and probably time) begins to exist, a materialistic explanation involving either material particles or energy fields, before space and time existed, makes no sense.

Now, some naturalists posit a prior material state or event before the Big Bang, as they do with eternal chaotic inflation or as they might do with the idea of an eternal “primaeval atom”. If naturalists take this track, then that state or event must have possessed the necessary and sufficient conditions for the production of our universe. But then that state or event in turn must have been produced by some earlier state of event possessing the necessary and sufficient conditions for producing it, and so on. Consequently, at some point in the past either an uncaused first material state or event must have occurred, or the necessary and sufficient conditions for the origin of the universe must have timelessly existed. In other words, either naturalists must posit an uncaused first event or they must posit that the necessary and sufficient conditions for the first event existed from all eternity in a timeless, changeless state. Neither of those options seem plausible, nor do they really make sense.

Physicist Sean Carroll, one of the most prominent proponents of naturalism, has acknowledged that naturalism has not explained the origin of the universe, precisely because Naturalism denies the existence of any entity external to nature. He suggests, however, that the origin of the universe does not necessarily require a causal explanation; it might “just be.” Nevertheless, because the evidence indicates that the universe has not existed infinitely, but instead began to exist, it would seem to require – by the principles of sufficient reason – a cause. Saying otherwise undermines one of the basic presuppositions of scientific investigation and indeed reason itself, namely, that “whatever begins to exist must have a cause.” Reason and scientific investigation depend upon the assumption that all material events do have causes. To say “it just is” is a cop-out and a violation of reason.

Revival of the God hypothesis

The Judeo-Christian tradition has long believed our universe was created by God, so theistic scientists naturally expected to find evidence of its beginning. Naturalism’s a priori dismissal of a non-natural cause of the universe made the idea of its eternal existence an inviting idea. However, over the last century, the evidence has swung back in the direction of theistic expectations.

Does the beginning of the universe provide a case for God’s existence? Does it confirm a theistic hypothesis?

Firstly, let’s consider the starting argument:

- Major Premise: A Judeo-Christian belief in a divine universal creator requires the universe to have had a beginning

- Minor Premise: We have evidence that the universe had a beginning.

- Conclusion: We have reason to think that the Judeo-Christian view of the origin of the universe and its affirmation of a divine creator may be true

This syllogism suggests that the Big Bang Theory provides epistemic support, though not deductive proof, for the hypothesis of Judeo-Christian theism. So, so far, the evidence that the universe had a beginning only provides abductive confirmation of the God hypothesis.

But I think we can take things further. Let’s put together a robust Cosmological argument – an argument that claims that the existence of God can be inferred from knowledge about the origin of the universe. Here goes…

The revised Cosmological Argument

The Cosmological argument for the existence of a creator was first proposed by one of the greatest medieval protagonists, Al-Ghazali, a twelfth-century Muslim theologian from Persia. He argued that the universe must have a beginning, and since nothing begins to exist without a cause, there must be a transcendent creator of the Universe. We can summarise his argument in three steps:

1. Whatever begins to exist has a cause of its beginning.

2. The universe began to exist.

3. Therefore, the universe had a cause of its beginning.

Let’s look at each step of this argument.

The first premise that “Whatever begins to exist has a cause” is pretty self-evident. Something cannot come from nothing at all. To claim that something can come into being from nothing is worse than magic. It assumes that there is no reason at all, like believing that things, say a horse or a house, can just pop into being without a cause.

To say that the universe just sprang into existence or that the Big Bang just happened, “there is no reason”, is about as scientific as saying the reason why coconuts fall to the ground is because they just do. It would be inconsistent to say that there is a reason and cause for everything except for the most important item of all, that is, the existence of everything: the universe itself. When you see a row of dominoes toppling before your eyes, you rightly assume that something caused the first domino to topple. So, our common experience confirms the truth of premise 1.

It’s understandable for someone to adopt a default stance of scepticism surrounding miraculous claims, but it would be wholly inconsistent for a sceptic to reject a claim of the virgin birth of the son of God, for instance, while unquestioningly swallowing the idea of the virgin birth of the universe. No matter how incredible one finds a claim of divine creation to be, a causeless beginning is still more absurd.

The second premise is something we have already argued throughout this essay, therefore, as a result, the conclusion that “the universe had a cause of its beginning” is self-evident.

Now some would argue that the universe is self-caused. For example, prominent atheist philosopher Daniel Dennett (even the late Stephen Hawking) agrees the universe has a cause. But he thinks it caused itself. The universe is the explanation for its own existence.

This is silly thinking. Something cannot create itself because to create itself it would already have to exist to do so. For example, if we say ‘X’ created ‘Y’, then we assume ‘X’ in order to bring ‘Y’ into existence. So if we say ‘X’ created ‘X’, then we assume ‘X’ in order to bring ‘X’ into existence, which doesn’t make any sense. Something fully creating itself is a logical impossibility, devoid of reason or evidence. The claim ‘X’ created ‘X’ in effect says “allow me to assume ‘X’ already exists and I’ll explain how ‘X’ then came into existence in a world in which ‘X’ already existed.”

While it would be wrong to assume the universe created itself, we still need to answer the fundamental question – what properties must the cause of the universe possess?

What properties must the cause of the universe possess?

Firstly, the cause must be itself uncaused because as we argued earlier, an infinite series of causes is impossible. It is therefore the Uncaused First Cause.

Secondly, the original cause must be separate and external to the universe. Why? Well for one, because we know something cannot fully create itself, since this is a logical impossibility. But also, If you observe any physical quantity, it will not explain its own existence. Nothing ‘in time’ is observed to be its own cause but rather is either an effect or an outcome of something beyond itself.

I think we can safely say that the first cause must be separate from the universe since all causes are separate from their effects. Since this universe is a reality of space, time, matter and energy, then what caused this universe must transcend all those. Causes that are physical or that are subject to scientific law presuppose time, space, and matter to exist. It could not have been some physical law in a higher-dimensional physical space, for that space would also require a beginning, as determined by the BGV theorem. Therefore, the logical extension is that the ultimate cause must be capable of existing without the world of space, time, matter and energy, and without being subject to the ultimate laws of nature. The universe’s immaterial cause was therefore timeless and spaceless.

As a side note, we can expand our definition of ‘the universe’ to include anything that begins to exist, requiring a cause, including what would be commonly called the multiverse.

It is also clear that the original cause could not have been an eternal lawlike force. In such a case, the circumstances that would cause the impersonal force to create a universe would have occurred infinitely far in the past because all chance circumstances would have transpired in an eternal reality. Therefore, the universe should be infinitely old, which it is not. This leads us to our third point – that the first cause must have had the power spontaneously to bring the world into existence as a first mover. This is an obvious issue for the naturalist. As we discussed earlier, if a cause is sufficient to produce its effect, then if the cause is there, the effect must be there too. Now the cause of the universe is permanently there, since it is timeless. So why isn’t the universe permanently there as well? Why did the universe come into being? Why isn’t it as permanent as its cause? Therefore, the first cause, having the power spontaneously to bring the world into existence as a first mover, must have genuine “free will,” not determined or triggered by any outside influence in order to act independent of any prior determining conditions. Now if free will is associated with consciousness, does that suggest that there was ultimate consciousness before the universe?

Of course, the idea of an unchanging free will being the agent of a changing cause poses its own quandary too, which we will address further below.

If we posit the concept of an ultimate consciousness (i.e.personal agent) with free will then that resolves the dilemma of explaining what kick-started the materialistic process for the origin of the universe. The concept of free will entails the idea that an agent with such freedom of ‘will’ can initiate a new chain of cause and effect without being compelled by any prior material conditions. The action of a free agent eliminates the need for an infinite regress or prior material states – and thus an infinite universe at odds with empirical observation. It is at least reasonable to consider the action of a free agent as a better explanation for the beginning of the universe.

In fact, positing the action of a free agent gives a perfectly cogent account of how the universe could have begun to exist consistent with our own experience of possessing free will. After all, free agents cause things to exist that did not exist before. Positing the choice of a free agent – a mind – provides, at the very least, a better scientific explanation for the beginning of the universe than naturalism and therefore atheism.

To summarise, the necessary properties of the original cause are that it must be:

- Uncaused;

- Immaterial;

- Timeless;

- Spaceless;

- Volitional;

- Immensely powerful;

Giving it a name

Does this ring a bell to you? We are brought not merely to a transcendent cause of the universe but to its Personal Creator – an agent for which the title ‘God fits perfectly.’ Theism has long drawn the conclusion that the physical world is the outflow of a conscious being – the power and wisdom of God.

One way to think about it is to envision God existing alone without the universe as changeless and timeless. His free act of creation is a temporal event simultaneous with the universe’s coming into being. Therefore, God enters into time when He creates the universe. God is thus timeless without the universe and in time with the universe.

This is admittedly hard for us to imagine. We reject this theistic proposition, not on the basis of rational or logical thinking, nor on the basis of science (since this deduction is based on experiential effects of personal agents), but on the basis of biased attitudes against any such evidence pointing towards God.

This revised cosmological argument for God, while perhaps not watertight, is certainly more convincing and far more plausible than naturalistic explanations. Not only (1) we should expect the universe to have a beginning if God exists, but also (2) the Judeo-Christian descriptions of God fit nicely with the properties of the original cause of our universe. But there is also a third key point, (3.) the basic premise of ancient teachings of Judeo-Christian literature accords with the latest views of Big Bang cosmology. One of the principal doctrines of the Judaeo-Christian faith is that God created the universe out of nothing a finite time ago. In the New Testament, there are two mentions of the plans of God existing before the beginning of time, which is striking in the sense that the singularity theorem implies time itself has a beginning. The Bible also mentions that at the creation God is stretching out the heavens, which runs consistently with the Big Bang Theory proposing that the universe is expanding.

There is a remarkable symmetry with the Judeo-Christian view.

Arno Penzias, the physicist who won the Nobel Prize for his discovery of the cosmic background radiation, made the remark concerning the Big Bang: “the best data we have are exactly what I would have predicted, had I nothing to go on but the first five books of Moses, the Psalms, the Bible as a whole.” In making this connection, Penzias evidently has in mind the famous words of the Bible, “In the beginning, God created…” When the Nobel Prize winner George Smoot announced the Big Bang ripples observed by COBE Satellite (NASA), he concluded that “there is no doubt between the Big Bang as an event and the Christian creation notion of creation from nothing.” Likewise, Quantum chemist and Nobel Prize nominee Henry F. Schaeffer III also concluded: “A Creator must exist. The Big Bang ripples and subsequent scientific findings are clearly pointing to an ex nihilo creation consistent with the first few verses of the Book of Genesis.” I am reminded by the words of NASA astronomer Robert Jastrow, who wrote:

“For the scientist who has lived by his faith in the power of reason, the story ends like a bad dream. He has scaled the mountain of ignorance; he is about to conquer the highest peak; as he pulls himself over the final rock, he is greeted by a band of theologians who have been sitting there for centuries.” Entirely expecting the universe to have a beginning since the very first words in scripture are “In the beginning.”

“But where did God come from?”

So far, God stands as the best explanation we currently hold for the origin of the universe. Or does He? Richard Dawkins has argued that if God is the reason why there is something rather than nothing, then “If God created the universe, who created God?’’

This objection shows a clear misunderstanding of the God hypothesis. While everything that begins to exist in this natural world requires an explanation for its existence, God did not begin. It’s not that everything has a cause, it’s that everything that begins has a cause. Something that exists outside of time would be eternal and therefore wouldn’t need a cause for its existence, since it never came into being. If God is without beginning or end (i.e. transcendent) then He didn’t have to begin, and if without a beginning, He didn’t need a cause. Something eternal doesn’t need a cause. We have good reason to believe the universe had a beginning, and therefore it is in need of a transcendent explanation, but the same does not apply to God.

Questions about God’s origin are therefore pointless. The five simple words of God’s response declared in the book of Exodus “I AM THAT I AM” suggests that God’s existence is an absolute reality. Being what He is, eternally existing, God could not fail to exist, and being who He is, all is constantly dependent on Him.

The doctrine of creation

Almost all the great classical philosophers saw the universe as arising from a transcendent reality. Sure, they had different approaches, but they all believed the universe is not self-explanatory, that it requires an explanation beyond itself. Rather than removing God, they understood that the existence of laws of physics strongly implies that there is a God who formulated such laws and ensures that the physical realm conforms to them.

Christianity is not an attempt to answer the unknown with fantasy. The Hebrew leader Moses had warned against worshipping other gods, bowing down to them or to the sun or the moon or the stars of the sky. For the prophets in the Bible, it was foolish to bow down to various bits of the universe, but they regarded it equally absurd to not believe in and acknowledge the creator God who made both the universe and them. I agree.

By accepting the doctrine of creation, we gain our fundamental understanding of the nature of the universe. The arguments for God’s existence (which include the one made in regard to the origin of the universe), together with the testimony of Scripture, point not only to God as the creator, but also show that the universe was not made from any preexisting material. The Apostle Paul, in Hebrews 11:3 wrote: “By faith we understand that the universe was created by the word of God, so that what is seen was not made out of things that are visible.” God is not an artisan who worked on preexisting materials—what Plato called the demiurge. Neither did God somehow create the universe out of himself – as creation ex deo. Instead, He alone is the maker of all things, so the truth of the matter is creation ex nihilo – creation out of nothing.

Because the creation includes the material universe, this repudiates eternal dualism (the idea that matter and spirit are eternal) and philosophical materialism/naturalism (the idea that the fundamental elements that comprise the physical universe are all that exist). Both of these ideas are common fruits of atheism. Because God did not make creation out of himself, this repudiates the idea that everything is god (pantheism) and various pantheistic New Age philosophies. The doctrine of creation also repudiates those philosophies that deify the universe, including, again, pantheism, witchcraft, and paganism. The creation of the universe rejects any notions that the universe is eternal. Further, having been created by an infinitely wise and rational God, various forms of the so-called “new” physics as well as chaos models are believed to be false. Finally, the doctrine of creation according to scriptural testimony attests to the idea that the universe was created with good intention. Its goodness is attested to numerous times in the Genesis narrative. This disapproves of Gnosticism and the obligations of that form of asceticism that illicitly seeks to reject all the amenities of the physical world as being in opposition to the godly life.

On a different level, the doctrine of creation gives us our fundamental understanding of mankind’s relationship to the universe. Several things follow from the fact that the universe is not divine but is God’s creation. First, nature is not something to be worshipped. This further repudiates various New Age, Wiccan, and pagan ideas. Instead, we are to have dominion over nature. In Genesis 1:28, God told Adam and Eve, “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it, and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over every living thing that moves on the earth.” This repudiates radical forms of environmentalism, where the interests of humans are subjugated to the interests of animals or elements. Our dominion over nature, however, does come with certain responsibilities. Being created in God’s image means, among other things, that we are responsible stewards over what God has entrusted to us. We care for the natural world as gardeners care for their plants, remembering that our managing of environmental resources should always be to the glory of God.

This is my conclusion: The Big Bang is one of the many lines of evidence that dismantles the atheistic take of a naturalistic viewpoint, while also providing support for the God Hypothesis. The God hypothesis, specifically via the doctrine of creation, in turn provides the foundational understanding of the nature of the Universe.

This essay is part one of two. Part two: God and Stephen Hawking. Is Quantum Cosmology God’s Undertaker?

Further reads:

- The Kalam Cosmological Argument – By Philosopher William Lane Craig

- The Return of the God Hypothesis – By Philosopher of Science Stephen C. Meyer