Imagine the situation — I am caught in a relentless struggle to make ends meet. Recently, our lives took a devastating turn when our home was consumed by a merciless fire. To compound our misfortune, the insurance company that should have been our safety net has collapsed into bankruptcy. With no other choice, I sold the charred remains of our land, but the proceeds were a mere drop in the ocean against the towering medical bills for my ailing father’s treatment.

Rent at the new house is very high, but as if fate hadn’t already dealt us enough blows, I was laid off from my job last week due to unforeseen budget cuts. Despite our best efforts to cut costs and embrace a minimalist lifestyle, the financial burdens continue to mount. Overdue rent is piling up, credit card debts are spiralling, and to make matters all the more unbearable, my wife has fallen into a deep depression under the weight of our financial crises.

Now, the situation has reached a critical point. Our landlord has issued us a final notice: pay the outstanding rent within the next seven days or face eviction. My wife and I are staring down the possibility of homelessness, with nowhere else to turn. What can we do in such a dire situation?

Then it occurred to me…

I can see Margaret, a little old lady, coming down the street, and she’s carrying a great big purse. She’s always carrying bundles of cash. She’s rich, snobby, rude and racist, the type of person who looks down on everyone. It suddenly occurs to me that she’s very little and old, and it would be incredibly easy to sneak up, knock her over and grab the purse. She wouldn’t even know it was me. I could finally clear my rent and maybe even my credit card debt.

Should I do it?

I start to rationalise the act, “She deserves this. After all, what goes around, comes around. She’s a horrible woman! For my wife’s sake, we need this money. It’s not like I’m going to physically hurt her.”

Masked up, I step out of my house, walk down the street, and as I wait in the perfect spot, I am arrested by a sudden surge of empathy. As I see her walk in my direction, I start to see a broken old woman, and I feel sorry for her. I step into the old lady’s shoes for a moment, imagining the trauma of the ordeal for a woman of her age. In this train of thought, I imagine how hard it would be for a woman of her age to get back up. She would suffer, and suffering isn’t nice. Despite my grievances against her, I find myself hoping for her wellbeing. The very thought of the act halts me in my tracks, and I choose to return home.

Herein lies an illustration of an other-regarding ethic — empathy. This response seems instinctively right and just. Many of us instinctively feel a duty to treat others as we would want to be treated ourselves, but from where does this instinct originate? What serves as the moral anchor for our obligation to alleviate the suffering of others; or to act in such a way as to put others before ourselves?

What is the ground of morality?

What grounds our sense of right and wrong, and what forms the foundation for our ethical commitments to others? This question invites us to examine our core beliefs about the nature of the world, our place in it, and the existence and role of God. Essentially, who or what is the source of moral principles?

Now, it’s essential to differentiate between moral values and moral duties:

- Moral Values: These are notions of ‘good’ and ‘bad’. When we talk about values, we assess whether something is inherently good or bad.

- Moral Duties: These concern the ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ of actions. A moral duty dictates what you ought to do or abstain from doing. Duties are about obligations and responsibilities dictated by moral principles.

The key difference lies in the sense of obligation—what we ought to do or not do. Certain actions are morally required or forbidden regardless of the consequences. For instance, if we witnessed a child being kidnapped, we would agree that we should intervene to stop it, even if it means risking our own safety or getting hurt in the process.

We all have a responsibility to live ethically. Moral values guide our actions and help us make the right choices. In essence, ethics expects our conformity. After all, shouldn’t we aspire to lead virtuous moral lives? The obvious answer is “yes”. However, this prompts a further question: what is the grounding for moral duties and obligations? What underpins our responsibility to live life in a certain manner and prioritise others’ welfare over our personal interests (i.e. an other-regarding ethic)?

With our inquiry defined, let’s first clear away some misconceptions. It’s sometimes said in Christian circles, a bit too dismissively, that atheists lack a moral compass, as if not believing in God renders ethical considerations irrelevant — “Atheists don’t believe in morality” a friend once asserted. Such oversimplified views miss the mark. For starters, it invites a pointed rebuttal: if Christianity is heralded as a bastion of morality, how do we then interpret the episodes of divinely endorsed violence, such as those described in the biblical narrative of the Israelites’ conquest of Canaan in Deuteronomy 20:13-17? My intention here is not to reignite debates over the moral justifications of Old Testament events, although that is a conversation worth having. Instead, my goal is to encourage a thoughtful examination of the underpinnings of morality, without falling back on hasty assertions. We should steer away from sweeping, brash statements.

It’s worth noting that many atheists lead “moral” lives. Many are kind, nice, and friendly. It’s entirely feasible to act relatively moral without believing in God. My interest, however, is focused on the possibility of an objective morality independent of God. To be clear, the question isn’t whether atheists can act morally. Many undeniably do most of the time. Nor is it whether atheists can formulate ethical frameworks. Many unquestionably have. And it’s not a probe into whether secular societies are more moral than religious ones. The sole query is whether an “objective morality” can exist without God. If it can’t, then what does that imply? The esteemed father of secular humanism, Paul Kurtz, encapsulated this question as follows:

“The central question about moral and ethical principles concerns their ontological foundation. If they are neither derived from God nor anchored in some transcendent ground, are they purely ephemeral?”

Are the treasured moral values that guide our existence simply societal conventions or individual preferences, like a predilection for certain foods? Or do they carry a validity and obligatory force independent of personal opinion, and if they are objective in this manner, what constitutes their foundation?

Now, we also need to clarify the distinction between objectivity and subjectivity. By objective, I mean something that exists “independent of human preference,” and by subjective I refer to something “dependent on human preference.” This ontological distinction will form the cornerstone of our discussion. Consequently, objective morality is something to be discovered, whereas subjective morality is invented. If objective moral values exist, it means that something can be good or bad regardless of human opinion. For example, declaring the Holocaust as objectively wrong means that it was wrong despite the Nazis believing it was right, and it would still have been wrong even if the Nazis had won World War II and managed to convince the world that the Holocaust was justified.

Evolutionary ethics occupy a unique position. While not dictated by human opinion, they are not entirely objective in the transcendent sense either. Evolutionary ethics suggest that certain moral behaviours and inclinations have emerged because they were advantageous for human survival and social cohesion. We will get into this shortly.

For centuries, the Judeo-Christian worldview has anchored our moral compass in the belief that God, the infinite and eternal Mind, is the ultimate definition of right and wrong. This conception of God as the architect of nature and the ultimate explanation behind human existence implies that moral laws are not arbitrary but deeply intertwined with the divine purpose. Yet, since the 18th century, belief in God in the West has been waning. This shift leads us to wonder: in the absence of a divine benchmark, what becomes the source of our moral understanding? In a world moving away from God-centric morality, who or what steps in to define what is ‘good’? Moreover, how do we establish the authority of these new moral values, and why should they be considered binding? These questions strike at the very heart of our quest to understand the foundations of moral law.

Ethics according to naturalistic evolution

One possible response is that the roots of our ethical inclinations can be traced back to our evolutionary history as social primates, without invoking God. Unlike solitary animals, our ancestors thrived in groups, which offered better chances of survival. Living in communities allowed early humans to collaborate on tasks like hunting, gathering, and protecting each other from predators. This social structure was favoured by natural selection, equipping us with the necessary social skills to interact and cooperate effectively.

This evolution towards sociality has led to the development of societal norms, refined through socialisation and cultural assimilation. These norms serve as survival instincts for coexistence and cooperation. Essentially, evolution has wired us to be social creatures, making life within communities not just more manageable but also more enjoyable and fulfilling when people are friendly and cooperative.

As a result, natural selection has fine-tuned our nervous systems to be responsive to others’ emotional states, emphasising the importance of social bonds for our wellbeing. Emotions play a crucial role in human evolution and societal bonding. Because emotions are contagious, we often mirror the feelings of those around us, sharing in their joy and sorrow. This is why comedies sometimes use laugh tracks—to get the audience in the mood. The notable exceptions to this rule are psychopaths, who can live wholly unaffected by the intense pain of others, but we typically view such antisocial personalities as abnormal.

Our social and altruistic tendencies form the core of our moral framework. Evolution has also driven us to seek happiness, making it a central goal of morality. Actions that promote human happiness are deemed moral because much of our joy comes from our interactions with others and our communities. Ignoring the happiness of others and focusing solely on our own can lead to hostility, which ultimately affects our own well-being. In this evolutionary perspective, personal well-being is deeply connected to the welfare of the community. Thus, even without invoking a divine figure, it’s clear how an ethic centred on others’ well-being could emerge from our evolutionary history.

Consider, for instance, a solitary tree in a desert. Its roots desperately search for water in the arid sand, while it is continuously bombarded by intense sun, dry winds, and relentless heat, all without the protective company of other trees. It struggles to survive. Contrast this with the same tree in a lush forest. Here, it shares the burdens of harsh conditions with numerous other trees. Their intertwined roots, collective shade, and mutual support significantly mitigate the harshness of their environment. This tree doesn’t just survive; it thrives.

Much like the lone tree, our pursuit of personal satisfaction, when devoid of communal considerations, can lead to a challenging and lonely existence. However, when we intertwine our lives with others, sharing in their joys and struggles, we establish a robust support system that bolsters our own happiness and resilience. Focusing solely on personal gratification, we risk resembling the lone tree in the desert: isolated and unfulfilled. In contrast, when we engage in the pursuit of collective happiness, we cultivate a more nurturing environment, which in turn amplifies our personal happiness.

Let’s explore a scenario to illustrate this point. Imagine someone accidentally drops their brand-new phone onto train tracks. At the same moment, a child is in danger on those same tracks. The person decides to rescue the phone instead of the child. It’s clear to everyone that prioritising the phone over the child’s safety is a terrible decision, highlighting a glaring lack of compassion. While this is an extreme example, it serves as a powerful reminder to reflect on our everyday choices. In many impoverished communities, even a small amount of money can significantly improve someone’s life. The funds we often spend on non-essential items could be life-saving for others. The issue is that we either fail to recognise the opportunities to help or, more likely, choose to ignore them to avoid feeling a sense of responsibility.

So, according to the moral evolutionary view, we are naturally inclined to seek and value communal harmony. This tendency is embedded in our genetic makeup, emphasising collective happiness over isolated personal pleasure. Our survival and prosperity depend on maintaining communal coherence and forming strong interpersonal connections. Actions that threaten communal harmony also undermine our own stability and contentment.

Interestingly, self-interest and societal interest often align. Our inherent sociability pushes us to prioritise societal well-being because we derive happiness from our relationships, whether casual or intimate. While solitude can offer satisfaction, our need for connection frequently draws us back to communal living. This perspective aligns with ethical egoism, where morality is tied to maximising self-interest. However, our self-interest is intertwined with our roles within communities, advocating for empathy, kindness, and care. Personal happiness and community welfare are two sides of the same coin, with individual success, survival, and growth depending on our ability to function effectively within a broader community.

As Sam Harris articulates:

“I believe that we will increasingly understand good and evil, right and wrong, in scientific terms, because moral concerns translate into facts about how our thoughts and behaviours affect the wellbeing of conscious creatures like ourselves… Taking others’ interests into account, making impartial decisions (and knowing that others will make them), rendering help to the needy – these are experiences that contribute to our social wellbeing. It seems perfectly reasonable… for each of us to submit to a system of justice in which our immediate selfish interests will often be superseded by considerations of fairness. It is only reasonable, however, that everyone will tend to be better off under such a system. As, it seems, they will.”

Essentially, our ethical perspectives are deeply entrenched in natural selection, a process eloquently summarised by Charles Darwin:

“The social instincts — the prime principle of man’s moral constitution — with the aid of active intellectual powers and the effects of habit, naturally lead to the golden rule, ‘As ye would that men should do to you, do ye to them likewise.’”

Much like bees demonstrating cooperative and self-sacrificial behaviours due to natural selection favouring these traits for the survival of the hive, humans have evolved similar behavioural tendencies, leading to a form of “herd morality.”

A distinctive aspect of this “herd morality” is our profound capacity for empathy and emotional understanding. As Jeremy Rifkin observes, “To empathise is to civilise. To civilise is to empathise.” This inherent capability allows us to prioritise others’ happiness and welfare, recognising their crucial role in the tribe’s overall survival and prosperity. Hence, happiness becomes an integral part of morality itself.

In this view, our moral framework isn’t derived from divine commands or abstract principles but is shaped by our biological makeup and the socio-biological demands of communal living. Our ethics are, therefore, practical tools for survival.

The pitfalls of evolutionary ethics

In all fairness, I do think that an evolutionary outlook on ethics can mostly explain the “other-regarding” values we highly regard in society. Over time, natural processes have shaped us to value well-being and happiness, which aligns with utilitarian ethics. Essentially, being kind and considerate often leads to a happier life, and acts of kindness can be rewarding in themselves. Many of us find joy in helping others.

If we define “good” as actions that promote the prosperity of conscious beings and “evil” as those that do the opposite, then questions about values become questions about well-being. Moreover, if human well-being is entirely dependent on the state of the human brain, it might be measurable through neuroscience. This means that science could potentially identify behaviours that are beneficial for human survival, providing answers to our ethical questions.

However, doubt begins to creep in.

Practical versus principled argument

First, it is crucial to distinguish between a practical argument for morality and a principled one. An evolutionary moral framework presupposes a duty towards actions that promote survival. There’s no question that acting in ways beneficial to survival is pragmatically advantageous. However, does this pragmatism translate into a moral obligation, a duty?

I’m not convinced. What justification, what principled reason, do we have for elevating survival and evolution to the zenith of virtue? Imagine I decide to step away from concerns about humanity’s future. What makes that morally wrong? If our existence is merely the by-product of randomness in an indifferent universe, does it truly matter whether we survive, thrive, decline, live, or die? In a universe devoid of actual purpose, all these outcomes bear the same weight, or rather, the same weightlessness. If nature is perceived as self-sufficient, without reference to a transcendent conscious entity like God, where can we locate the ontological foundation for our ethical values?

Starting from inert, unconscious matter and perceiving the universe’s history as a sequence of random collisions and self-emerging natural laws that form increasingly complex arrangements of matter, leads to a sobering conclusion. We end up with a reality that is, at its core, merely a grand tapestry of rearranged matter. In this context, the world lacks an inherent purpose or meaning. It lacks context. Morality, then, is reduced to a functional role, serving as a useful tool to achieve an indiscriminate end, rather than an objective obligation.

If the universe is merely a cosmic accident with no inherent purpose, can there truly be a moral obligation or duty towards the survival and evolution of humanity? Morality, in this context, is simply a practical guideline that we, as sentient beings, have adopted to navigate existence. If our ethical sense is merely a tool to help genes propagate, then it does not dictate what we should or shouldn’t do. In the grand scheme of the cosmos, there is no actual requirement or binding duty for us to uphold the survival and evolution of humanity as a moral imperative. This notion is a delusion. It only takes one person to wake up and embrace this lack of moral duty for chaos and suffering to be unleashed.

So, the point is that from an atheistic perspective, where nature is all-encompassing and the physical explains everything without referencing anything “outside,” moral values transform into subjective and debatable opinions rather than objective truths. Evolution might justify morality functionally, which certainly counts for something (and I don’t want to dismiss that), but it doesn’t clearly substantiate the notion of moral values as binding or dutiful. This implies that in such a worldview, adherence to principles of evolutionary ethics isn’t mandatory, potentially leading individuals to act destructively without naturalistic grounds for objection. Acts of chaos, violence, theft, or oppression are not inherently wrong in this context.

Moral arguments with no truth value

Assuming that moral values are products of biological evolution, our moral beliefs are selected for their survival value, not their truth. This means our moral instincts may help us survive, but that doesn’t make them inherently true. From an evolutionary perspective, talking about moral truths is meaningless. Evolutionary ethics suggests that human cooperation is just a practical survival strategy chosen by natural selection. This doesn’t make it inherently good; it just means it’s effective.

Labelling behaviours like sharing, cooperation, and altruism as “moral” or “good” is like calling a tin opener moral or a doorstop good. They are simply functional. For example, behaviors like rape and incest are harmful to human flourishing, so evolutionarily, they are seen as unfavorable, but not objectively wrong. In the animal kingdom, such behaviours are common and can be crucial for survival.

As Charles Darwin speculated:

“If men were reared under precisely the same conditions as hive-bees, there can hardly be a doubt that our unmarried females would, like the worker bees, think it a sacred duty to kill their brothers, and mothers would strive to kill their fertile daughters; and no one would think of interfering.”

If morality is merely a tool for survival without inherent meaning, then in drastically altered circumstances where isolation becomes the most effective survival strategy, our values of cooperation and mutual regard would become irrelevant. This is because evolutionary-based moral values are entirely dependent on our environment and societal conditions. They lack an immutable essence and instead adapt to the demands of survival.

For instance, if Earth underwent drastic changes in a few hundred years, altering the survival strategy, our moral framework would inevitably shift. Actions we currently see as reprehensible could, under new conditions, be considered virtuous.

To help explain, imagine you survive a shipwreck and find yourself stranded on a deserted island with just one other person. Back in your normal life, you’re used to cooperation, sharing resources, and living peacefully with others. Laws against theft and violence help keep everything in order. But now, things are different. You and your fellow survivor discover a small stash of food. In your old life, the right thing to do would be to share the food. But here, sharing might mean both of you slowly starve as the limited food runs out.

In this desperate situation, you might decide to keep all the food for yourself, even using force to protect it. Back home, this would be seen as theft and aggression—completely immoral actions. But on this solitary island where survival hinges on every decision made, these so-called “immoral” actions could become the very strategies that keep you alive. Thus, actions deemed immoral in a communal context may become essential strategies for survival when circumstances dramatically shift — and therefore the “right” thing to do.

This raises a vital question. If morality is flexible and ever-changing, subject to the whims of survival necessity, can we genuinely regard any moral claim as ‘wrong’ or ‘right’ in an absolute sense? Or are these just placeholders for the utilitarian words “effective” or “ineffective”?

Picture a lion in the African Savannah, swiftly taking down a zebra. We don’t call this murder; it’s simply a survival mechanism. Similarly, think of a great white shark in the ocean, forcefully mating with a female. We don’t label this as rape; it’s a natural act of reproduction. In the animal kingdom, these behaviours don’t have moral implications. They are just parts of the natural order, observed but neither obliged nor forbidden.

Now, you could argue that humans stand apart from other species due to our advanced moral intuition. We possess a unique ability to reflect on our actions. This capability implies that we have the potential for moral progress. However, integrating the idea of “progress” into a naturalistic worldview presents a challenge. The naturalistic worldview claims that all aspects of reality, including human existence, are the result of physical laws acting on matter. It’s all self-referential. This framework lacks any transcendent context or external benchmarks for evaluating progress. Therefore, when we speak of “progress” within this worldview, we encounter a paradox. The concept of progress implies movement towards an external, objective goal. Yet, such a directive abstract purpose seems at odds with a naturalistic worldview, which inherently denies the existence of any benchmarks beyond the physical.

So yes, evolution can account for shifts in moral behaviour. It provides a means of understanding why certain behaviours might become more prevalent over time due to their survival benefits. But it falls short of establishing an objective foundation for moral principles. This limitation stems from its inherent design: evolution is a description of biological changes over time, not a guideline for moral conduct. Acts of rape and murder cannot be labelled as truly wrong — that wouldn’t make sense. In a naturalistic universe, the moral progress we aspire to may merely be a dance of atoms and energy without any ultimate significance. While this doesn’t necessarily nullify the importance we subjectively attach to our moral actions, it does underscore the potential absence of objective moral duties/principles by which our “progress” could be justified.

Morality beyond the survival of the fittest

My next objection is that I’m not entirely convinced that evolutionary ethics can fully explain the wide range of moral values we hold today. While it might support ideas like mutual care and compassion, it could also justify opposite behaviours in certain situations.

For instance, we can agree that evolution, when viewed through the lens of social behaviour, can indeed foster a form of “herd morality.” This suggests that traits such as empathy and care for others have been naturally selected because they enhance group survival. By helping and protecting each other, we increase our collective chances of survival and reproduction, furthering the propagation of our genes.

However, an interesting paradox arises when we consider different groups or hierarchical ranks within a population. Evolutionary dynamics may encourage us to empathise and cooperate with those within our “in-group” of the evolutionary hierarchy, however, the same evolutionary process can also foster competition, conflict, or even indifference towards “out-groups,” especially if they’re perceived as weaker or less fit. This is often where the concept of evolutionary ethics comes under scrutiny.

The fact is, evolution inherently creates hierarchies within species based on differences in physical and intellectual capacities, reproductive success, and access to resources. This process groups individuals into stronger and weaker subgroups, shaping complex social structures. So, cooperation within groups promotes survival, while competition among groups drives the evolution of traits.

In-group favouritism, where individuals prefer and cooperate with their own group, strengthens group cohesion and survival. Conversely, competition for limited resources leads to conflicts with out-groups. From an evolutionary standpoint, stronger groups are incentivised to compete with and dominate weaker groups to secure resources, ensuring that their traits and genes are more likely to be passed on to future generations. This competition is a natural outcome of evolutionary pressures.

This situation raises a moral dilemma: from an evolutionary ethical standpoint, stronger groups dominating weaker ones is a natural outcome of survival of the fittest. However, such behaviour is considered reprehensible as it contradicts our deeply ingrained principle of universal human rights. This raises a crucial question: How can we objectively condemn acts of mass oppression, such as the genocide in Sudan, where a dominant ethnic group victimises a weaker one? From a purely evolutionary standpoint, I can’t find a satisfactory objection. If it’s evolutionarily beneficial for the strong to overcome the weak during resource scarcity, why do we express outrage when powerful nations dominate weaker ones? Is our indignation truly warranted, or just a matter of emotion? It is a significant leap of faith to argue that humans are nothing more than the product of an unguided evolutionary process — in which progress is made through the strong overpowering the weak in a survivalist struggle — while concurrently asserting that the strong should not harm the weak out of respect for every individual’s dignity.

If humans are mere biochemical entities, then it logically follows that human worth is determined by material substance and functional utility. Evolution champions the survival of the fittest, and adhering strictly to this principle can prove severely brutal. In a world with finite resources, evolution offers no protections for the weak, whether they are physically, mentally, or intellectually challenged, thereby leaving them susceptible to death, violence, and destruction. Following exactly this evolutionary logic, the Nazi regime justified sending disabled and homosexual people to die in concentration camps on the basis of their reduced ability to provide strong progeny to further help society survive and flourish. This harsh reality is evolutionarily beneficial, since it operates on the principle that the strong should dominate and eradicate the weak when resources are scarce. Thus, in times of resource scarcity, which will be reality sooner or later, this could be perceived as the “moral” course of action under evolutionary ethics.

Furthermore, numerous scientific studies have demonstrated correlations between genetic makeup and various antisocial behaviours. For example, the presence of a particular gene receptor has been linked to a decreased likelihood of boys completing their schooling, even with additional support. Genetics also influences susceptibility to diseases, addictions, and other problematic behaviours. In a strictly naturalistic worldview, it could be argued that it would be socially and economically more efficient to prevent individuals genetically predisposed to less-productive lives from passing on their genes (i.e. from having children). Yet, history has shown us that eugenics, though scientifically efficient, is morally repugnant. Our moral intuition that eugenics is wrong must be rooted in a source beyond a strictly rational cost-benefit analysis guided by evolutionary principles.

So, while evolutionary ethics can provide valuable insights into human behaviour and emotions, it falls short in offering a comprehensive explanation for our moral values, particularly the belief that all humans have inherent worth and should be valued equally.

The logical inconsistency in the evolutionary basis for morality presents a dilemma. If you believe that morality is entirely rooted in the realities of the evolutionary process, which advocates for the strong to dominate and eliminate the weak when resources are limited, then practices like genocide and eugenics can sometimes be justified as they could help our species thrive, no matter how reprehensible they appear to us. Alternatively, if you believe that such practices are inherently wrong irrespective of any survival advantage they may confer, then you must acknowledge a moral framework that transcends a purely naturalistic worldview. In this case, we adopt an ethical system that recognises certain actions as always immoral, regardless of whether they aid the propagation of our genes. Ultimately, you can’t have it both ways—either morality is dictated solely by evolution as a tool for survival, or it is grounded in something higher that supersedes the brutality of natural selection.

Subjectivity of ethical norms

Another concern for me arises when morality is equated with subjective states associated with happiness. Don’t get me wrong, emotions are, without a doubt, a key part of our humanity. They facilitate our ability to connect, communicate, empathise and build communities, all of which are essential for our survival and evolution. However, equating morality with emotional states associated with happiness or wellbeing introduces a significant layer of subjectivity and potential inconsistency. It’s not uncommon to hear phrases like “if it feels right, do it” or “if it feels wrong, avoid it.” But then how do we reconcile instances when we have opposing feelings about the same issue?

In contemporary society, there’s a growing trend of discerning ‘goodness’ through the lens of emotions. Duty and authority are gradually being replaced by utility and self-expression, blurring of ‘being good’ with ‘feeling good.’ Thus, the ethical standards people abide by are increasingly dictated by their emotional state rather than universally applicable moral principles. Our educational systems, in many cases, fall short of providing a robust intellectual foundation for ethical values, inadvertently promoting scepticism towards the objective nature of moral duties. This vacuum of moral guidance often gets filled by media, which amplifies sensuality and manipulates emotions to propagate specific narratives. This shift in ethical perspectives plunges moral philosophers into a sea of relativism, where life resembles a pinball game. In this game, rules are scant and primarily serve to enhance the player’s enjoyment. In the end, morality is reduced to mere tools to maximise pleasure.

I think the critical challenge is to discern a stable foundation for morality amidst the turbulent sea of emotions. While it’s undeniable that emotions contribute to our survival and evolution by fostering social bonds, the risk lies in allowing them to become the ultimate arbiters of moral value. The task, then, is to recognise the role of emotions in our moral lives without surrendering the search for more stable ethical anchors. It’s a wise saying that “emotions make great servants but terrible masters.” It’s a balancing act between acknowledging the value of emotional resonance in morality, while also recognising the inherent instability that comes from relying solely on feelings as the bedrock of ethics.

Naturalistic fallacy

My final objection focuses on the fundamental mistake of turning to science, specifically evolutionary sciences, as a source of moral guidance. The supposition that science can dictate ethics fails to acknowledge the inherent neutrality of science.

While science can provide us with supposed facts and observations about the natural world, can it really attribute moral value to these findings? Can you discover moral values under a microscope or in a Petri dish? It was Albert Einstein who once said that “you can speak of the ethical foundations of science, but you cannot speak of the scientific foundations of ethics.” Scientists, of course, can conduct experiments and record data, but will science itself instruct whether they should be honest when reporting their findings?

A reductionist perspective that reduces us to nothing more than a complex assortment of atoms leaves little room for the existence of moral duty. An evolutionary understanding of ethics creates preferences, not moral truths and this distinction should not be lightly dismissed.

Science is descriptive, not prescriptive. It aims to explain the world based on observable evidence, not to dictate how the world should be. The fact that certain behaviours or tendencies have evolutionary roots does not automatically imbue them with moral or ethical worth in modern societies. This approach risks falling into the trap of the naturalistic fallacy, which erroneously infers moral conclusions from natural facts.

Scottish philosopher David Hume (1711–1776) highlighted the significant philosophical distinction between what is and what ought to be, commonly known as “Hume’s law.” According to Hume, we cannot logically move from descriptive statements (explaining what is) to prescriptive ones (suggesting what ought to be done). Science excels at describing the world, illuminating how things are, but it does not prescribe how things should be or offer guidance on how we should live our lives. Essentially, we cannot derive a moral “ought” from a scientific “is.” When people claim that a scientific fact implies a moral directive, they are likely introducing values from outside the scientific realm.

Don’t get me wrong – science is incredibly useful for understanding human well-being. It provides valuable insights, just like it does for understanding mental health during a pandemic or the benefits of strong social connections. However, scientific findings don’t inherently tell us what we should or shouldn’t do morally. While science can show which actions might cause harm, it can’t tell us whether we should avoid those actions. How can science declare that it’s morally wrong to harm someone?

To address this gap, proponents of naturalism frequently invoke the concept of “wellbeing” as an objective moral standard. Yet, they consistently falter in establishing an objective, consistent authority to substantiate this stance. Who or what precisely determines the criteria for wellbeing? Is it up to your discretion? Moreover, what immutable authority compels us to prioritise human wellbeing and, by extension, human evolution? While it may intuitively seem correct to highly value wellbeing and evolution, within a purely scientific framework, there is no objective obligation to do so within a purely scientific framework.

Summary

Evolutionary ethics has its merits—it offers valuable insights into altruistic behaviour within communities and species. It explains how cooperation and social cohesion can provide a survival advantage, leading to the development of moral behaviours like empathy and cooperation. These behaviours are seen as mechanisms that enhance individual wellbeing within specific groups. People in cooperative groups tend to survive better and experience greater happiness and prosperity, which suggests that our moral rules often aim to maximise overall happiness and wellbeing. From this perspective, the foundation of ethics is deeply rooted in the human drive for survival and happiness.

However, evolutionary ethics faces several challenges. One significant issue is the difficulty in extending ethical norms beyond tribal or group boundaries. If evolution favors the dominance of stronger groups over weaker ones during resource scarcity, the existence of moral values that transcend group boundaries seems dubious.

Another challenge is the subjectivity of these ethical norms. If environmental conditions change to favor individual survival over group survival, established moral values could be completely overturned. This suggests that evolutionary ethics provides a functional argument for survival rather than a principled, objective argument for moral values.

Moreover, the concept of moral duty or “oughtness” is not inherent in evolutionary ethics. Even though social rules may serve functional and advantageous purposes for survival and growth, this doesn’t necessarily imply that they are “binding”. Without a universally binding moral duty, our moral choices become reflections of personal or societal preferences – and that’s all.

In this view, the concept of ‘ought’ — the idea that certain actions are morally required — loses its foundation. Actions and thoughts are seen as entirely products of natural processes, intrinsically neutral, leading to the conclusion that they are not inherently good or bad. From this perspective, moral categories are perceived as illusions — constructs that, despite being treated as facets of objective reality, are not supported as such by this worldview. They are mere evolutionary inventions, created to facilitate social cohesion, serving our aimless survival. This implies that, just as you might construct arguments in favour of certain moral principles that help us survive, it is equally plausible to dismiss all such notions. In this framework, neither stance — advocating for certain moral principles or rejecting them outright — can claim correctness, since each is lacking a definitive grounding.

Considering the ultimate indifference of the universe, where all things inevitably conclude, the valorisation of survival as a virtue becomes a leap of faith, not a fact grounded in objectivity. Therefore, the functional argument falls short of providing a principled basis for morality—especially when adopting a reductionist view of reality, where the universe is seen as a self-contained, purely material entity devoid of any ultimate meaning beyond delusional attachments.

Lastly, the evolutionary approach to ethics appears primarily self-regarding rather than other-regarding. Even seemingly selfless acts are based on the assumption that strengthening the community ultimately serves the individual’s interests. Thus, the core of the evolutionary approach to ethics rests on personal benefit. Consequently, naturalistic evolution fails to justify objective, other-regarding ethical duties.

Atheist admissions

Many atheistic philosophers have accepted the belief that morality is an illusion, an artificial construct without grounding in any objective truth. This perspective contends that human life holds no intrinsic value or purpose, seeing humans as accidental products of a random and indifferent universe. This reductionist approach dismisses the idea of a divine creator and, with it, the concept of universal moral values that transcend human judgement. Such a perspective suggests humans are essentially like biological “machines for propagating DNA.” Machines, quite clearly, have no ethical obligations.

In the absence of an ultimate standard for right and wrong, ethical duties often reflect personal preferences and societal norms, making moral judgments subjective. For instance, what one culture considers morally acceptable might be deemed unacceptable in another. A moral norm in India might be abhorrent in France, and a standard in America could be outrageous in Iran. Different societies have unique interpretations of morality: in the Middle Eastern world of Islam, moral truth is revealed; in the Far Eastern traditions of Hinduism and Buddhism, it is intuitive; in the Western world, it is reasoned; and for the secularised Western individual, it is felt. This variation raises the question: why should your personal moral code hold more authority than mine?

Atheist philosopher Alex Rosenberg concedes that “[our] core morality isn’t true, right, correct, and neither is any other. Nature just seduced us into thinking it’s right.” If moral principles are merely the result of various subjective factors—like evolutionary, societal, and parental influences—then you’re not inherently obligated to uphold them.

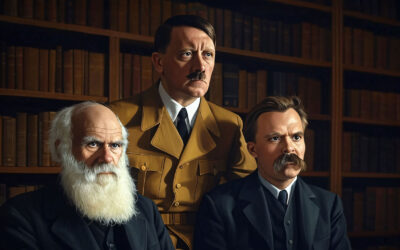

History has shown us that figures like Hitler, Stalin, and Mao, who committed unspeakable atrocities, believed they were accountable only to themselves. Adolf Hitler, for instance, saw himself as morally superior and believed he was acting in accordance with natural laws by advancing human evolution. He subscribed to a ruthless interpretation of Darwin’s principles of natural selection, asserting that conflict and struggle were necessary for evolutionary progress. He rationalised his horrific actions, including the extermination of those he deemed “inferior,” as serving a higher purpose: accelerating the advancement of what he believed to be a superior Aryan race. In his mind, societal struggle and warfare were not just unavoidable but necessary to weed out the “weak” and allow the “strong” to dominate, a concept he tied closely to his vision of racial purity and supremacy. This belief system created a framework where war and violence were not just justified but glorified as tools for the supposed betterment of human evolution. While many argue that Hitler’s belief was a gross misinterpretation and misuse of the principles of evolution, the question remains: Was it? In purely evolutionary terms, it’s debatable. Atheists share the notion of no God and a wholly material existence, which has led to the erosion of moral absolutes and the justification of any political theory.

During World War II, as it became clear that Nazi Germany would lose, a senior party officer openly questioned the value of Germany’s treaty obligations, asking “what, after all, compels us to keep our promises?” This troubling question illustrates the Nazi’s frightening moral philosophy and raises serious implications for the absence of objective moral duties. The great novelist, Fyodor Dostoevsky, tried to show that if God’s existence is denied, we fall into complete moral relativism, in which no act, regardless of how heinous, can be condemned as objectively wrong by hard-line atheists. Dostoevsky’s magnificent novels “Crime and Punishment” and “The Brother Karamazov” powerfully illustrate these themes. Joel Marks, Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at the University of New Haven, puts the issues simply and succinctly:

“[T]he religious fundamentalists are correct: without God, there is no morality. But they are incorrect, I still believe, about there being a God. Hence, I believe, there is no morality.”

The roots of such thinking, at least in the modern period, can be readily traced back to the nihilism of Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900). Whilst it is true that Nietzsche didn’t completely reject the possibility of a kind of “higher morality” that would guide the actions of “higher men”, he was dismissive of all universal and transcendent ethical systems, whether grounded in the natural world, human psychology or a Divine Being. All such systems, in Nietzsche’s thought, are merely man-made customs, for “there are no moral facts at all.” The ethical consequence of this is that the distinction between good and evil is relative, arbitrary, and ultimately illusory. As Nietzsche writes in On the Genealogy of Morals:

“One has taken the value of these ‘values’ as given, as factual, as beyond all question; one has hitherto never doubted or hesitated in the slightest degree in supposing ‘the good man’ to be of greater value than ‘the evil man,’ of greater value in the sense of furthering the advancement and prosperity of man in general… But what if the reverse were true?”

Nietzsche’s answer to this question is that “everything evil, terrible, tyrannical in man, everything in him that is kin to beasts of prey and serpents, serves the enhancement of the species ‘man’ as much as its opposite does.” Such a conclusion is necessary, for humanity is, in the final analysis, driven by an impersonal, irrational and decidedly amoral “will to power.” As Nietzsche expressed it in Beyond Good and Evil:

“[Anything which] is a living and not a dying body… will have to be an incarnate will to power, it will strive to grow, spread, seize, become predominant—not from any morality or immorality but because it is living and because life simply is will to power…. ‘Exploitation’… belongs to the essence of what lives, as a basic organic function; it is a consequence of the will to power, which is after all the will to life.”

The renowned atheist philosopher David Hume, known for his critical views on religious belief, famously argued that “reason is, and ought only to be, the slave of the passions.” Consequently, ethical theories cannot appeal to objective moral facts, but only to subjective emotions and feelings. Similarly, the eminent atheist Bertrand Russell admits “the impossibility of reconciling ethical feelings with ethical doctrines”, and that ethics is “reducible to politics in the last analysis.”

Numerous other voices may be added to those of Nietzsche and Russell. For example, Canadian atheistic philosopher, Kai Nielson, despite a valiant attempt to construct a utilitarian ethic without God, eventually concludes his quest as follows:

“We have not been able to show that reason requires the moral point of view, or that all really rational persons, unhoodwinked by myth or ideology, need not be individual egoists or classical amoralists…. Pure practical reason, even with a good knowledge of the facts, will not take you to morality.”

Indeed, “the very concept of moral obligation”, wrote the atheistic ethicist Richard Taylor, is “unintelligible apart from the idea of God.” The spectre of nihilism lurks behind every form of ethical naturalism. Alexander Rosenberg happily wears the label “nihilist” and argues that all honest atheists should do the same. Lest any uncertainty remain about what this means for morality, Rosenberg spells out the implications:

“Nihilism rejects the distinction between acts that are morally permitted, morally forbidden, and morally required. Nihilism tells us not that we can’t know which moral judgements are right, but that they are all wrong. More exactly, it claims they are all based on false, groundless presuppositions. Nihilism says that the whole idea of ‘morally permissible’ is untenable nonsense. As such, it can hardly be accused of holding that ‘everything is morally permissible.’ That, too, is untenable nonsense. Moreover, nihilism denies that there is really any such thing as intrinsic moral value… Nihilism denies that there is anything at all that is good in itself or, for that matter, bad in itself.”

A case for objective morality

Perhaps you’re reading this and thinking, “So what? Yes, I believe morality is illusionary and subjective. What’s the problem with that?” The issue, as I see it, is that most people who subscribe to atheistic naturalism don’t actually live like this. Including you. Your everyday approach to morality doesn’t really reflect what you claim to believe about it.

For instance, consider someone who neglects to keep their own promises, yet feels a surge of anger when others fail to honour commitments towards them. This person denies the universality of a ‘right’ or ‘wrong’, yet demands others adhere to a code of behaviour they themselves do not regard as ultimately binding or true. This apparent contradiction suggests an underlying cognitive dissonance: even while they openly reject the existence of objective moral duties, their actions subtly suggest that deep down, they might actually recognise them.

If you truly believe that morality is just an illusion, try saying it out loud. Stand in front of a mirror and declare, “Rape isn’t actually wrong,” or “Murder, though perhaps not evolutionarily beneficial, isn’t inherently evil.” Say, “Genocide may not be ideal in some evolutionary sense, but it’s not truly forbidden.” Feel the weight of these words. Could you repeat them in front of victims of these heinous acts? I know I’m being provocative; it’s a test of your convictions. When faced with the brutal reality of these statements, does your gut not revolt, hinting at a deeper moral understanding?

To say that certain things are really and truly evil, there needs to be a solid foundation, an objective basis to call them evil. This isn’t just about intellectual debates; it’s about confronting the disturbing implications of a worldview that denies objective moral duties and responsibilities. The unease you feel is telling—it suggests that, despite a veneer of philosophical scepticism, there’s an instinctive moral sense within you that recoils at such assertions.

The shift towards philosophical naturalism, which aims to detach morality from the divine, has seemingly eroded the logical foundation of morality. Yet, it’s clear that our moral values are more than just social conventions or personal preferences. The inherent pull of goodness suggests a deeper moral reality, making a purely atheistic perspective not only unsettling but untenable. Certain actions appear universally good or evil, implying an objective moral standard that atheism struggles to explain. Rape is wrong, regardless of any evolutionary benefit or drawback it may have in a circumstance; regardless of culture, race, or history.

If you were born into a huge tribe of Nazis and the old lady was one of only a few Jews, would you be wrong to beat her up? If yes, then this answer from common social customs is flawed. We all intuitively feel that beating up an old lady would still be objectively wrong, no matter how many people thought otherwise, or even if it served an evolutionary benefit. As Saint Augustine said, “Right is right even if no one is doing it; wrong is wrong even if everyone is doing it.” Generally speaking, the way we react to particular crimes or negligence bears witness to the conviction that in our more honest moments, we really do believe moral values are somehow valid and binding, independent of personal opinion or preference.

An objective moral law entails three specific features. Firstly, they serve as an authoritative guide for actions, regardless of tastes, preferences, desires, self-interest, etc. Secondly, there is a prescriptive obligation that follows from within the system and brings a sense of “oughtness” and of imperatives; it dictates how things should be. Third, morality is universal. Moral principles are not arbitrary and personal, but are public, applying equally to all people in relevantly similar situations. That’s what objective moral law entails.

Proving the existence of objective morals is not as challenging as it might seem. In today’s diverse society, many students are hesitant to impose their values on others. Yet, they hold certain principles—like tolerance, open-mindedness, and acceptance—as if they are universally good. They believe it is objectively wrong to force your values on someone else. Additionally, most people agree that acts such as rape, torture, and child abuse are not just socially unacceptable but are moral atrocities. On the other hand, behaviours like love, generosity, and self-sacrifice are universally praised as genuinely good. These examples highlight that our moral experiences point to a belief in objective moral duties, even if we find it difficult to fully explain this belief.

I recall a discussion where a pastor shared his experience of helping abused children. A panellist on the show responded, “What counts as abuse varies from society to society, so we can’t really use the word ‘abuse’ without considering its historical context.” The pastor replied, “Call it what you like, but child abuse is damaging to children. Isn’t it wrong to harm children?” The panellist had no response. Doesn’t this highlight the absurdity of a relativistic worldview?

Let’s take this further: consider the Hindu practice of suttee (burning widows alive on their husband’s funeral pyre), the ancient Chinese custom of foot binding, or the atrocities of the Crusades and the Inquisition. Most people would agree that these practices are inherently evil, regardless of cultural or historical context.

The more we go through in life, the more we see that evil is not just an abstract concept but a real, destructive force. It has the power to corrupt the purest of intentions, to destroy the most cherished relationships, and to end the deepest forms of love.

Acknowledging the existence of evil inherently suggests the presence of its opposite — good. For the dichotomy of good and evil to be meaningful and consistent, there must be an objective standard defining them. This objective moral law serves as the benchmark for distinguishing between good and evil. The existence of an objective moral law logically implies the presence of a moral lawgiver, as morality is deeply connected to intentionality. Morality fundamentally revolves around meaning, and meaning requires intention—a mind. Thus, the idea of a moral lawgiver justifies the existence of a transcendent Mind, a conscious entity capable of establishing moral standards for the world, which theists refer to as God.

By embracing this perspective, you recognise that aspects of reality, especially principles of justice, are imbued with profound sense and meaning.

The Christian worldview suggests that the nature of God, the basis of moral law, is revealed through Jesus Christ. The gospel recounts the story of a passionate God who ventures beyond himself, relinquishing his divinity, and humbling himself to engage with humanity, ultimately enduring suffering for our redemption. As the judge of all, He took on the penalty for humanity’s moral failures, showcasing His immense love. This divine love is the cornerstone of Christian ethics and the source from which all standards of right and good character flow.

Jesus articulated that the highest form of love is the willingness to give your life for the benefit of others. This principle, central to Christian doctrine, is rooted in the life and teachings of Jesus Christ, who exemplified it through His selfless act of sacrifice for humanity’s redemption. This type of love, known as Agape love or gift-love, transcends self-interest and personal preservation. It is a selfless love that prioritises the welfare of others, even to the point of paying the ultimate price to achieve a greater good.

Agape love, as demonstrated by Jesus, is more than just an act of kindness; it has the power to transform and bring about the highest good and wellbeing for others. From a Christian perspective, this “good” or “wellbeing” is not just about physical or material prosperity but is deeply connected to the spiritual realm. It means having a profound relationship with God, experiencing His love, grace, and fellowship on a deeply personal level. Therefore, the Christian understanding of “good” or “wellbeing” goes beyond earthly concerns. It involves a state of spiritual harmony with God, nurtured by practising Agape love.

The Apostle Paul stated unequivocally:

“The one who loves another has fulfilled the law. The commandments, ‘You shall not commit adultery; You shall not murder; You shall not steal; You shall not covet’; and any other commandments, are summed up in this word, ‘Love your neighbour as yourself.’ Love does no wrong to a neighbour; therefore, love is the fulfilling of the law.”

In the Christian worldview, moral rules, while important, are secondary to the overarching principle of love. Love is not just a sentiment or fleeting feeling, but an active choice rooted in the very nature of God. The paramount moral principle, “Love your neighbour as yourself,” is presented as a universal mandate. It transcends cultural, social, and religious boundaries, applying to all of humanity. This tenet is authoritative, stemming from the highest divine authority. It is not a mere suggestion or guideline, but a binding directive expected to be followed by everyone.

Moreover, this principle carries an ethical obligation, a prescriptive duty. It implies that we have a responsibility to express love through tangible actions, such as kindness, compassion, and selflessness, towards others. This love is not limited to those who are easy to love, like friends and family, but extends to strangers, enemies, and those who are often marginalised or overlooked in society. It is universal, authoritative, and bears a prescriptive obligation.

I hope I am not misunderstood. Contrary to what many in the Church believe, I don’t subscribe to the traditional Divine Command Theory, which views Christian morality as a list of ancient do’s and don’ts. I believe that many Old Testament commands were specific to the Israelites and not necessarily universally applicable today. However, this doesn’t mean I disregard these teachings. In fact, I strive to honour and understand why they were written — to adhere to the spirit behind the rules.

The essence of Christian morality, as I see it, is more than just following rules. It’s more about embodying the ultimate person, the ultimate reality — God. This is exemplified in Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount, where he reinterprets Old Testament edicts, saying, “You have heard it said… but I say to you…” This reframing underscores the deeper purpose behind these moral directives, acknowledging that sometimes these rules might not be universally applicable or might lose their intended significance.

This insight is crucial to understand. I hold the view that Old Testament moral commandments, while acting as guides to an underlying objective moral ethic, should not be seen as rigid in themselves. Rather, they point towards a deeper ethical principle. This principle demands a level of reverence and understanding that surpasses the literal interpretation of the rules. It suggests that true morality is about discerning and embodying the spirit and ethos behind the commandments, applying them contextually rather than adhering rigidly to their letter.

Jesus summarised this objective principle, saying, “So in everything, do to others what you would have them do to you, for this sums up the Law and the Prophets.” The essence of all laws and teachings is to treat others with the same care and consideration you would wish for yourself. This is the ethic that Jesus embodied. While specific rules may change and evolve over time, the core of Christian morality is the principle of love, as exemplified and defined in the gospel, which forms the foundation of an objective moral framework grounded in God Himself.

Moral rules, therefore, are ongoing developments to help us adhere to this underlying ethic. They are dynamic guides that assist followers in aligning with this fundamental ethical foundation. This distinction is crucial, especially when addressing criticisms that equate the changing nature of specific Biblical laws with subjective morality. Such criticisms overlook the essence of Christian moral teaching, which is not tied to the unchanging nature of specific rules but rooted in the perpetual principle of love — defined and expressed through Jesus.

While some advocate for “self-love,” often equated with the pursuit of personal happiness, the essence of Christian teaching asks us to redirect this self-focus towards others. Happiness is undoubtedly a desirable state; we all seek it. However, Christ’s commandment encourages us to extend the love we have for ourselves to our neighbours: “Love your neighbour as you love yourself” (Matthew 22:39). If you are enthusiastic about seeking your happiness, show the same enthusiasm for the welfare of those around you. Use the intensity of your pursuit of personal happiness as the benchmark for your efforts to better the lives of others.

Are you hungry? Give your neighbour food. Are you lonely? Be a friend to someone who has none. Are you suffering? Relieve the suffering of others. Make your degree of self-seeking the measure by which you invest in and love others. Project the depth of your self-regard onto the welfare and good of others. This is an overwhelming standard that requires grace from God to live out, as it is the foundation of Christian ethics.

Therefore, the gospel is not only a medium for reconciliation between humanity and God but also a compass for moral direction, providing a model of genuine love and an ultimate objective towards which we should aspire. A popular saying suggests that humanity is beholden to two sovereign masters — pain and pleasure. In the Christian worldview, these are not true sovereigns. Instead of promoting an unending pursuit of pleasure or a futile avoidance of pain, Jesus beckons us to embrace a path of sacrificial love.

The contrast is clear and compelling: in a society that encourages us to “be ourselves, look after ourselves, express ourselves, trust ourselves, and treat ourselves,” Jesus counsels, “deny yourself, take up your cross daily, and follow me.”

The atheist dilemma: Morality or amorality?

There’s a lot more to explore about Christian objective morality. This essay mainly critiques the atheistic foundation for morality instead of diving deep into the theistic perspective. This focus is because debates often scrutinise Christian views on morality but rarely challenge naturalistic and atheistic viewpoints to the same extent.

For now, it’s important to understand that Christians believe morality is ultimately grounded in God, but believing in God isn’t necessary for moral behaviour. We need to differentiate between moral epistemology (how we understand right and wrong) and moral ontology (the principles that define what is truly right or wrong)

Imagine two individuals navigating a complex maze: one is a seasoned cartographer with a detailed map and compass, while the other relies on gut feelings and past experiences. Both might reach the exit, but their methods differ significantly. Similarly, an atheist might live a moral life based on intuition, societal norms, or personal experiences—like the intuitive wanderer. The atheist practises morality but lacks a concrete foundation for why certain actions are right or wrong. In contrast, a theist understands morality as grounded in the nature of God, providing an objective basis for moral duties. This is like the cartographer using a map and compass, knowing why certain paths are correct. Thus, both the atheist and the theist live morally, but while the theist has a firm and rational grounding for their beliefs, the atheist’s beliefs, though often correct, are based on subjective grounds that are flimsy and questionable. The atheist believes in moral duties and responsibilities but for the wrong reasons.

While atheists may offer alternative theories to rationalise the functional benefits of our moral intuition, they often fall short of providing a principled justification. Moreover, the ethical rules that can be accounted for through naturalistic explanations don’t fully align with the ethical principles most of us hold today. Our moral intuition possesses a distinctive quality that extends beyond any evolutionary advantage. It urges us to consider the welfare of those who cannot reciprocate, even beyond our community or tribe.

Our moral compass isn’t solely directed by societal consensus or personal happiness but is grounded in the conviction that all humans have intrinsic worth deserving of protection and respect. The morality we adhere to is more than just a byproduct of evolution, although evolution accounts for something. Christian morality does not prioritise survival value over individual value. Instead, it compels us to value individuals, even those on society’s margins or those who cannot contribute to the species’ survival, such as the elderly or infertile.

The core conviction that every individual possesses inherent value, regardless of their social standing, is deeply rooted in the Judeo-Christian worldview. Judaism introduced the concept that all humans are made in the image of God and Christianity proclaims that God intends to glorify, commune, and unite with humans. These are world-changing ethical contributions to society. These doctrines manifest as beliefs in the equality and irrevocability of human value and our responsibility to prioritise others’ needs. Such a community-centric ethic, grounded in charity, is integral to the Christian worldview, but its religious origins are often forgotten.

Even though they aren’t religious themselves, important thinkers like Jürgen Habermas and Jacques Derrida recognise how much Christian ethics have shaped our modern moral ideas. Habermas pointed out that values we hold dear today — like democracy, equality, and human rights — actually come from Jewish ideas about justice and Christian teachings about love. Derrida suggested that without the biblical concept that humans are made in God’s image, we might not even have the idea of “crimes against humanity.”

The belief that all people have value and that society should take care of those in need came from cultures that believed in a personal God who wanted a loving relationship with His creation. Even though modern secularism has distanced itself from the idea of a divinely orchestrated universe, it has largely retained these biblically derived moral principles. An objective, “other-regarding” ethical system persists even amid the dwindling influence of organised religion.

This leaves us with an important question: Can we sustain an objective, “other-regarding” ethical system without acknowledging its root — the Christian worldview that provides the ontological grounding for this ethic? Extracting the fruits of a worldview — its ethics and morals — while disregarding its nourishing roots may render the ethical system groundless and its principles arbitrary.

Nietzsche provided a particularly incisive analysis of this dichotomy. He questioned the validity of conventional morality in a world devoid of a personal, transcendent reality. Without such a reality, there remains no universally applicable standard to distinguish between right and wrong.

“Judgements, judgements of value, concerning life, for it or against it, can, in the end, never be true: they have value only as symptoms, they are worthy of consideration only as symptoms; in themselves such judgements are stupidities. One must by all means stretch out one’s fingers and make the attempt to grasp this amazing finesse, that the value of life cannot be estimated.”

In such a worldview, subjectivity becomes the rule, and objectivity is denied, else one must deny the existence of all morality and value. Moral relativism steps in, leading to a point where declaring one aspect of life as “good” and another as “bad” rests solely on individual preference and cultural consensus.

There remains a logical link to nihilism that emerges when a universal moral compass is dismissed. Our society, though committed to moral convictions, lacks a robust foundation for distinguishing virtue from vice. As a result, our moral intuitions float, detached from any solid ground. This situation presents a conundrum for atheists: How do they prevent ethical relativism when moral experiences lose meaning without an objective moral order, and this order loses meaning without God. Theism not only interprets these moral intuitions but also anchors them in an unchanging moral reality. As the famous philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein succinctly put it, “Ethics, if it is anything, is supernatural.” Hence, attempting to reconcile atheism with morality often leads to intellectual dissonance.

Ultimately, if God does not exist, objective moral values and duties do not exist. With secularism at the helm, the West risks collapse. Secular thought, grounded in inherently amoral assumptions, sees morality as separate from real knowledge.

On the other hand, recognising the existence of objective moral values allows for the possibility of God’s existence. How? The esteemed philosopher John Frame suggests that ethical obligations only arise within the context of interpersonal relationships, placing personhood at the core of morality. This implies an intrinsic connection between moral values and the essence of personhood. Thus, if moral authority is exclusively in the realm of persons, absolute moral authority must be the domain of an absolute person, presupposing the existence of an absolute personality for absolute moral standards. This reasoning necessitates a personal, self-aware, purposeful God—not just as a philosophical luxury but as a prerequisite for valuable, rights-bearing, and morally accountable human beings. This concept of God as personal, self-aware, purposeful, and defining good, forms the indispensable foundation for the emergence and sustenance of morally responsible human beings. Thus, any discussion on objective moral duties invariably loops back to the necessity of God.

In theological terms, human moral experience is seen as part of God’s general revelation. Our moral impulses, sense of justice, and capacity for empathy—all part of our moral existence—are seen as facets of divine revelation. Our ability to engage with moral questions, bear ethical responsibilities, and recognise moral authority emanates from our intrinsic connection to a divine, moral authority. The Apostle Paul articulates this, stating, “Even Gentiles, who do not have God’s written law, show that they know His law when they instinctively obey it, even without having heard it. They demonstrate that God’s law is written in their hearts, for their conscience and thoughts either accuse them or tell them they are doing right” (Romans 2:14-15). And later, “So then each of us will give an account of himself to God.”

From a Christian perspective, atheism is seen as a resistance to God’s special revelation, especially the fact that God will judge all through Jesus Christ. Rejecting this means rejecting the only way for us to be saved from the coming wrath against our moral repugnance, by turning to Jesus Christ, who died to secure our forgiveness and rose again to provide eternal life to believers.

The predicament for every atheist is stark: The choice is between renouncing actual moral duties — the logical conclusion of atheism — or forsaking atheism in favour of some form of theism. Atheism entails embracing amorality and rejecting God’s special revelation, while the latter allows for upholding morality and acknowledging the existence of a necessary moral authority.