Unravelling Scientism

“Science is the only way we know to understand the real world,” posited Dawkins. “There is no reason to suppose that science cannot deal with every aspect of existence,” expounded chemist Peter Atkins.

Scientism advances the notion that “Science is the only way.” Essentially, it argues that science is not merely one approach among a myriad of others for obtaining truth, but rather the very bedrock of truth and rationality itself—the cornerstone for ascertaining anything at all. As Nobel Prize-winning chemist Harry Kroto stated, “Science is the only philosophical construct we have to determine TRUTH with any degree of reliability.”

I admire the fervour of these scientists. Scientific inquiry has undeniably facilitated a myriad of remarkable accomplishments and discoveries which have radically transformed our understanding of the natural world. Nonetheless, a wellspring of truth may also spawn intellectual mirages and conceptual muddles. While I greatly admire the scientific endeavour, I harbour concerns about the ramifications of an excessive reliance on, and unbridled confidence in, science as the sole legitimate source of knowledge encompassing all aspects of human life and, ultimately, all human challenges.

It is prudent to elucidate the meaning of the term ‘science.’ While a comprehensive definition remains elusive, there exists a general consensus on at least one characteristic of science that ensures the applicability of its methodologies—specifically, empirical verification. Derived from the Greek word “empeiría,” which translates to “experience,” empiricism is a contemporary epistemological theory predicated on experience gleaned from the five senses (i.e., sight, taste, touch, hearing, and smell). In the context of science, empirical verification is typically attained through experiments that observe and quantify physically embodied entities (matter) with the aim of extrapolating (abstracting) their verifiable properties to yield precise or definitive descriptions.

Scientism, which should not be confused with science, is the idea that everything in existence is made of physical matter that follows specific laws, and that all phenomena are essentially based on this. In simpler terms, scientism believes that reality is entirely physical. As a result, scientism often involves a commitment to naturalism, reductive materialism, or emergent materialism, trying to define all knowledge in a way that includes this particular viewpoint.

Naturalism is commonly understood as the ontological perspective asserting that everything is physical, material, or within the realm of natural sciences. This view suggests that concepts like consciousness, goodness, evil, beauty, and purpose can be reduced to, or even explained away by, the naturalistic domain. A naturalistic assumption posits that purposeless laws, matter, and energy, rather than a deity, form the fundamental reality from which everything else originates. Consequently, naturalism relies solely on natural science, however fallible, to provide an account of reality. Therefore, naturalism is predicated upon a core set of beliefs voluntarily accepted as the foundation for all inquiry.

The Scottish philosopher David Hume proposed a theory of knowledge known as radical empiricism. Empiricism maintains that observing the natural world through the five senses provides the most reliable path to knowledge. French philosopher Auguste Comte argued that true knowledge is attained only when natural phenomena are explained by reference to natural laws or strictly material mechanisms.

Through the lens of scientism, no events are fundamentally nonphysical; thus, in the future, all aspects of history, literature, and arts—not to mention law, politics, and human relationships—will be explained away or by the elementary laws of physics. Scientism contends that every facet of reality within which human life exists will be resolved by physical science. This implies that any scholarly endeavour not rooted in the requisite construct of ideas must be dismissed as metaphysical speculation, subjective bias, or, ironically, religious orthodoxy. Consequently, a central tenet of scientism asserts that only demonstrably scientific knowledge qualifies as genuine knowledge, while all else is considered nonsense.

Scientism dismisses most significant forms of transcendence, such as the concept of God. If materialism encapsulates the essence of reality in terms of matter and purposeless laws, and physics is all-encompassing, then there is no need for, and indeed no space for, transcendence. Within scientism, transcendent ethical realities or principles are nonexistent. Moral realism and deontological ethics lack substance or foundation. As scientism extends its influence into human sciences, the humanities, and even religion, it calls into question all transcendence, along with trans-situational values and morality in general, offering in return a strictly utilitarian moral landscape.

When scientific knowledge is deemed the only authentic and verifiable form of knowledge, it renders much of our self-perception meaningless. This impacts our view of human nature, leading us to see ourselves as purely mechanical, materialistic organisms. Since materialists believe that matter and energy form the fundamental realities from which everything else originates, they deny or explain away the existence of immaterial entities such as God, free will, the human soul, and even the human mind, when conceived as separate from the physiological processes occurring in the brain. Such confidence would be reasonable only if every aspect of reality could be deduced from matter and physical laws, making it accessible to study by natural science. This confidence reminds us that scientism’s rejection of metaphysics is itself metaphysical in nature. Scientism insists on a naturalist, materialist, and largely mechanistic worldview that associates more predominantly with the left hemisphere’s mode of thinking. However, this does not imply that such a worldview is solely ‘left-brained,’ as real-world thinking and perception require the integrated functioning of both brain hemispheres.

It is at this point that I posit scientism functions as a form of secular religion. Scientism exudes and fosters an unwavering faith in the capacity of natural science to generate knowledge and resolve all problems confronting humanity. It assumes the mantle of religion in its pursuit of ultimate explanations. Scientism embodies precisely what “exclusive humanism” requires: a means of accounting for the ultimate without appealing to transcendence—an explanation for the “way things are” that remains firmly rooted in the “immanent frame.” However, akin to many religions, scientism can also manifest as a narrow and oppressive orthodoxy of thought, which, I contend, hampers the field of science it professes to revere. This will be the focus of this essay.

C.S. Lewis’s Critique of Scientism

Science, when properly comprehended, offers a range of experimental and observational techniques that allow for drawing reasonable conclusions within its domain. However, scientism takes a critical leap by asserting that the methodologies employed by science are the exclusive reliable means for acquiring knowledge about ourselves and the world. Consequently, this perspective suggests that scientists should be the ultimate authorities on public policy, morality, and even religious beliefs.

C.S. Lewis concurred that the scientific method was a valuable way to amass information and advance knowledge. Nonetheless, he refuted the notion that it was the only, or even the superior, method for accomplishing these goals. For Lewis, science holds a position at the table, but not a privileged one. Importantly, science provides information, not wisdom, and is incapable of addressing some of our most pressing questions or guiding us in utilising the knowledge it yields.

Lewis emphasised the necessity of differentiating between two distinct types of knowledge: ‘Scientia’ and ‘Sapientia.’ ‘Scientia’ pertains to knowledge of the physical world, obtained through scientific observation and experimentation, and is concerned with facts, quantity, repeatability, and matter. In contrast, ‘Sapientia’ encompasses knowledge derived from intuition, common sense, and revelation, leading to transcendent understanding and addressing issues of meaning, value, and purpose. According to Iain Gilchrist’s interpretation of brain lateralization, ‘scientia’, representing a more analytical and detailed-oriented approach to understanding, might be associated more with the left hemisphere’s mode of operation. On the other hand, ‘sapientia’, symbolising a broader, more contextual and integrative comprehension, might be more in line with the right hemisphere’s style of processing.

According to Lewis, conflating these two ways of knowing may lead to serious misconceptions about reality. Scientism, with its emphasis on reductionist, abstract thinking, may align more predominantly with the left hemisphere’s approach—can sometimes overlook the autonomy and value of different forms of knowledge, including those that are more holistic and context-driven. When conducting a scientific experiment to gain insight into the physical realm, it is crucial to prevent intuition or dogma from interfering. Conversely, when the scientific method is inapplicable, as is the case with many of life’s pressing issues, we should turn to wisdom and revelation. While ‘Scientia’ is valuable for pursuing certain truths, it is essential to acknowledge its limitations—a notion that the philosophy of scientism neglects.

Science elucidates the mechanisms behind phenomena but offers little insight into the purposes driving these events. As Lewis posited, “In science, we are only reading the notes to a poem; in Christianity, we find the poem itself.” Lewis maintained that when science encroaches on questions of purpose and morality, it can become perilous, potentially usurping the longstanding tradition of ‘Sapientia,’ or wisdom. The question arises: Is the philosophical foundation of scientism sufficiently robust to entrust it with the increasingly complex ethical dilemmas of the modern age? In his A Guide for the Perplexed, E.F. Schumacher offers this evaluation of scientism:

“The maps provided by modern materialistic scientism leave all the questions that really matter unanswered; more than that, they deny the validity of the questions… the ever more vigorous application of the scientific method to all subjects and disciplines has destroyed even the last remnants of ancient wisdom… For it is being loudly proclaimed in the name of scientific objectivity that ‘values and meanings are nothing but defence mechanisms and reaction formations’… that man is ‘nothing but a complex biochemical mechanism powered by a combustion system which energises computers with prodigious storage facilities for retaining encoded information.’”

Scientism, as a philosophical stance, bears the potential to facilitate dehumanisation due to its dismissal of transcendent values. As Lewis posited in The Weight of Glory, this approach engenders a perilous reductionism:

“The critique of every experience from below, the voluntary ignoring of meaning and concentration on fact, will always have some plausibility. There will always be evidence, and every month new evidence, to show that religion is only psychology, justice only self-protection, politics only economics, love only lust, and thought only cerebral bio-chemistry.”

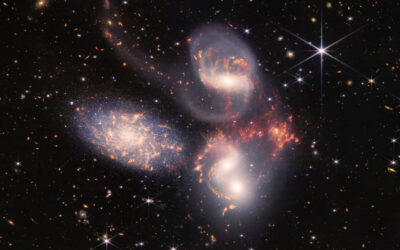

Lewis posits that a comprehensive understanding requires not only an examination of the facts but also an exploration of their underlying meaning. Even as we delve into factual analysis, we traverse merely a fraction of the path to true comprehension. In Lewis’s The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, young Eustace Scrubb confidently asserts, “In our world, a star is a massive ball of flaming gas.” However, the sagacious old man offers a nuanced perspective. “Even in your world, my son,” the man replies, “that is not what a star is, but only what it is composed of.”

Moreover, scientism’s assertion that only science can uncover truth while dismissing the contributions of philosophy and religion is inherently self-defeating. This claim is a belief about science, rather than a fact derived through scientific inquiry. The notion that science can explain everything is, in itself, a philosophical stance. It constitutes a philosophical statement about science that paradoxically argues against philosophical statements, and it cannot be verified through scientific methods alone. To further illustrate this point, we can construct an argument using the OED definitions of “science” and “scientism”:

- Science is “the intellectual and practical activity encompassing those branches of study that relate to the phenomena of the physical universe and their laws…”

- Scientism is “the belief that only knowledge obtained from scientific research is valid…”

- “The belief that only knowledge obtained from scientific research is valid” is not, itself, derived from “the intellectual and practical activity encompassing those branches of study that relate to the phenomena of the physical universe and their laws…”

- Therefore, if the premise of “the belief that only knowledge obtained from scientific research is valid…” is, itself, valid, it is false by definition and consequently self-refuting.

If scientism’s foundational principle is true, the statement expressing scientism must be false. When prominent scientists like the late Stephen Hawking made sweeping statements such as “philosophy is dead… Scientists have become the bearers of the torch of discovery in our quest for knowledge,” they and their supporters exhibited a philosophical ignorance symptomatic of scientific hubris. The declaration “philosophy is dead” is not a scientific statement. Naturalists, who dismiss or reduce other domains of knowledge such as philosophy or theology, fail to recognise that naturalism is itself a philosophical view about science.

Beyond Scientism: The Implications of Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems

In addition to C.S. Lewis, another influential figure who challenges the idea that all knowledge can be acquired through scientific inquiry is Kurt Friedrich Gödel. A logician, mathematician, and philosopher, Gödel ranks alongside Aristotle and Gottlob Frege as one of the most important logicians in history. In 1931, Gödel introduced his Incompleteness Theorems, which consist of two results in mathematical logic that expose the inherent limitations of any formal axiomatic system encompassing basic arithmetic.

Gödel’s First Incompleteness Theorem asserts that within any consistent formal system capable of expressing basic arithmetic, there will always exist true statements that are unprovable within the system. In other words, certain true mathematical statements cannot be proven using the axioms and rules of inference inherent in the system. This theorem implies that no scientific model can provide a complete and comprehensive understanding of the natural world, as there will always be true statements about reality that cannot be proven within the confines of these models.

Gödel’s Second Incompleteness Theorem posits that in any consistent formal system capable of expressing basic arithmetic, the system’s consistency cannot be proven internally. This theorem carries significant implications for science, as it suggests that we cannot definitively establish the consistency of the mathematical models that underpin our scientific theories.

In the context of scientism, Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems highlight the intrinsic limitations of what can be known or proven using the scientific method exclusively. Science depends on formal systems, like mathematics, to describe and model the natural world. Gödel’s groundbreaking theorems reveal that such systems have built-in limitations, meaning that some truths about the world will always remain beyond the reach of scientific inquiry.

Can Science Explain Everything?

Richard Feynman, a Nobel laureate, insightfully described science as a method for answering questions framed as, “if I do this, what will happen?” This reveals the playful nature at the heart of scientific inquiry, driven by curiosity, exploration, and experimentation. The scientific technique is fundamentally “try it and see.” Then you put together a large amount of information from such experiences and infer conclusions. However, any question, be it philosophical or otherwise, which cannot be framed in a way that allows for experimental testing, falls outside the realm of science. Thus, science is more about probability than absolute truth. Feynman is characteristically clear on this:

“All scientific knowledge is uncertain. This experience with doubt and uncertainty is important. I believe it is of very great value and one that extends beyond the sciences. I believe that to solve any problem that has not been solved before, you have to leave the door to the unknown ajar. You have to permit the possibility that you do not have it exactly right. Otherwise, if you have made up your mind already, you might not solve it… So what we call scientific knowledge today is a body of knowledge of varying degrees of certainty.”

It is probably fair to say that many scientists are, like myself, “critical realists”, believing in an objective world which can be studied and who hold that their theories, though not amounting to ‘truth’ in any final or absolute sense, give them an increasingly firm handle on reality. Science can give an increasingly tighter grip on the physical world, but therein lies the rub: can the whole of reality be fully explained by the mere physical?

When faced with phenomena that seem to defy explanation by natural sciences, should we acknowledge the need for a more open and varied pursuit of truth, extending beyond material sciences while still maintaining reason. Or, alternatively, should we remain patient, holding onto the hope that one day, material science will ultimately unravel all the mysteries that surround us? Essentially, we are asking about the boundaries and potential of scientific inquiry.

Can the sciences fully account for the laws of logic and mathematics?

Far from it.

Can the sciences explain the origin of the fundamental laws of nature?

Hardly.

Has quantum cosmology shed light on the emergence of the universe and its existence?

Barely scratching the surface.

Can the sciences explain why our universe appears finely-tuned for the existence of life?

Still a mystery.

Have the sciences unlocked the enigma of consciousness?

Not even close.

Do the sciences offer a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between the mind and the brain?

A persistent puzzle.

Can the sciences provide a basis for moral truths?

Not a chance.

Can the sciences address the ultimate questions of meaning, purpose, and values in human life?

Inherently limited.

Are scientists prone to accept any idea as long as it doesn’t stem from religious thought?

Often, yes.

Will science ever be able to explain these mysteries? It remains uncertain. The crux of the matter lies in whether reality extends beyond mere materialism. My intuition suggests that it does, but now it’s time to engage my intellect and present a series of topics that, in my opinion, may forever elude scientific explanation, even in principle.

Proposition 1: Science cannot explain itself

First and foremost, science faces a unique challenge: it cannot fully explain itself. This conundrum arises from the existence of at least three fundamental preconditions that underlie the practice of science:

- A thinking mind

- A world to explore

- A rational intelligibility that establishes harmony between the mind and the world

For the process of thinking to occur, there must be a thinking mind, a world with phenomena to contemplate, and a logical connection between the two that enables understanding. Science must also assume the existence of objective truth, which corresponds with reality, and the general reliability of our sensory and cognitive faculties for discerning that truth. Without these metaphysical prerequisites, the practice of science would be rendered impossible.

These three essential features suggest that science is a sophisticated human engagement with a rationally ordered world. The way one interprets these metaphysical preconditions directly influences one’s perception of science, the range of its methodologies, the nature of knowledge it can provide, and the questions it can reasonably address. These presuppositions exist prior to science in the hierarchy of knowledge, and thus, by definition, they cannot be subjected to scientific investigation since they are pre-scientific. They are the very foundation upon which science is built.

Examining, critiquing, and defending these foundational assumptions behind science is a philosophical endeavour rather than a scientific one. Just as a building’s structural integrity relies on the strength of its foundation, the conclusions drawn from scientific inquiry cannot be more certain than the presuppositions upon which science itself is based.

Albert Einstein’s profound awe at the intelligibility of the cosmos led him to declare, “The most incomprehensible thing about the universe is that it is comprehensible.” Implicit in the notion of the universe’s intelligibility is the existence of a rational mind capable of recognising it. Confidence in the reliability of our human mental processes and their ability to provide information about the world is essential for all intellectual inquiry, not just scientific study. This belief entails the understanding that nature and its workings can be captured and conveyed through language, a remarkable and awe-inspiring feat.

These fundamental convictions are indispensable to all thought processes. One cannot question their validity without relying on reason and the laws of logic, as they form the bedrock upon which all intellectual inquiry is built. It is crucial to highlight that science often rests on the foundations of logic and mathematics. By appealing to these laws, science often presupposes their existence but cannot justify them. Laws of logic and basic mathematics are warranted by direct rational awareness, independent of sensory experience. In contrast, the sciences justify their laws and theories through empirical observations. Thus, the laws of logic and mathematics hold greater rational certainty than scientific claims, as they are considered a priori, necessary truths, while scientific claims are a posteriori, contingent truths.

Nobel laureate Eugene Wigner marvelled at the profound connection between mathematics and natural sciences, stating, “The enormous usefulness of mathematics in the natural sciences is something bordering on the mysterious, and there is no rational explanation for it… it is an article of faith.” The intricate relationship between mathematics and physics is difficult to dismiss as mere coincidence. Oxford mathematician Sir Roger Penrose emphasises this point, asserting that the remarkable harmony between mathematics and physics cannot be attributed to random natural selection of ideas. Instead, a deep, underlying reason must exist for this relationship:

“It is hard for me to believe… that such superb theories could have arisen merely by some random natural selection of ideas leaving only the good ones as survivors. The good ones are simply much too good to be the survivors of ideas that have arisen in a random way. There must be, instead, some deep underlying reason for the accord between mathematics and physics.”

Science alone cannot account for this phenomenon. As physicist John Polkinghorne explains, “Science does not explain the mathematical intelligibility of the physical world, for it is part of science’s founding faith that this is so.” Thus, renowned physicists Wigner and Polkinghorne both acknowledge the essential role that faith—or trust—plays in the foundation of scientific inquiry.

The practice of science relies on the acceptance of certain presuppositions. One such belief is the principle of the uniformity of nature, which asserts that events occurring today will most likely happen again tomorrow. Although there is no guarantee that the sun will rise every day, this expectation is founded on reasonable faith and is indispensable to the progress of science.

When contemplating the uniformity of nature, our attention is drawn to the fundamental laws of nature. The existence and precise nature of these laws, however, cannot be explained solely through scientific inquiry, as all scientific explanations presuppose their existence. These foundational laws serve as brute givens, essential for explaining other phenomena scientifically but not themselves explicable through scientific means. While scientific experiments can identify these laws, they cannot account for their existence, as science itself is dependent on them.

The explanation for the universe’s rational intelligibility relies not on whether one is a scientist, but rather on one’s perspective as a theist or naturalist. Theists argue that the intelligibility of the universe is grounded in the ultimate rationality of God, who created both the real world and mathematics, as well as the human mind with its capacity for observation and abstract thought. Consequently, it is not surprising that mathematical theories formulated by human minds, created in the image of God’s mind, find practical application in a universe designed by the same creative force. This understanding is coherent and logical.

By embracing the theological grounding of God, we can provide a more comprehensive and plausible explanation for the philosophical assumptions underpinning science. A theistic perspective attributes the rational order and structure of the universe to a purposeful Creator who has imbued the cosmos with meaning and intelligibility. This view supports the idea that the universe operates under predictable laws, allowing us to investigate and understand its workings systematically.

In contrast, adopting an atheistic worldview that denies the existence of God, design, purpose, or meaning can undermine the crucial philosophical assumptions that form the foundation of science. Without a rational and purposeful origin, it becomes difficult to explain why the universe adheres to discernible laws and exhibits the level of order necessary for scientific inquiry. The consistency and predictability of natural laws, which are fundamental to the scientific method, seem inexplicable if they emerged solely from a purposeless, random process.

Furthermore, the atheistic perspective struggles to account for the remarkable capacity of human cognition to apprehend and make sense of the world around us. The striking congruence between the human mind and the rational structure of the universe is more readily explained by a purposeful Creator who designed both. This harmony between our cognitive abilities and the external world is essential for the pursuit of scientific knowledge.

In light of these considerations, atheism as a worldview may lack the necessary foundation to objectively justify the pursuit of science. Without a coherent explanation for the existence of consistent natural laws and the human mind’s capacity to understand them, the atheistic perspective risks rendering the scientific enterprise arbitrary or coincidental.

Conversely, belief in a rational Creator provides the primary foundation for the scientific enterprise, offering a coherent explanation for the universe’s intelligibility and the human mind’s capacity for discovery. By acknowledging a purposeful origin, we can understand the rational basis for scientific inquiry and appreciate the harmony between our cognitive faculties and the order inherent in the cosmos.

In conclusion, it is crucial to emphasise that the conclusions of science cannot be more reliable than their underlying presuppositions. Scientism, by its very nature, tends to dismiss these presuppositions, as they are primarily philosophical rather than scientific. As a result, scientism inadvertently undermines the very foundations of science itself, jeopardising the entire structure.

The philosophy of scientism, which is distinct from science, can paradoxically become an adversary of science. Scientism overlooks the fact that science depends on presuppositions beyond its domain. To claim that science is more fundamental than philosophy or other fields, such as theology, is to assert that a claim based on its assumptions holds greater merit than the strength of the assumptions themselves. In reality, however, a claim is only as valid as the assumption upon which it rests. Since these assumptions are philosophical rather than scientific, philosophy holds a primacy over science. Consequently, it is erroneous to assume that science takes precedence over other disciplines.

Science is built upon foundational ideas concerning the value of knowledge, relying on the belief that the pursuit of knowledge is intrinsically valuable. However, if we are merely purposeless chemical conglomerates, governed by deterministic laws and destined for eventual oblivion as the universe reaches total entropy, what makes science, progress, and the pursuit of knowledge so remarkable? Science alone cannot provide an answer to this question. A more comprehensive worldview is needed, one that transcends the narrow scope of naturalism. In the search for meaning and understanding, both science and its practitioners require a broader perspective.

Proposition 2: Science cannot explain the origin of the universe

The question whether the universe had a beginning is one that has puzzled humanity for centuries. Both philosophical and scientific evidence suggests that the universe did indeed have a beginning, making this idea not only philosophically coherent but also scientifically grounded. To summarise, there are multiple lines of scientific evidence to support this conclusion:

- The Second Law of Thermodynamics: According to this law, the amount of useful energy in the universe is irreversibly decreasing. If the universe were infinitely old, all its useful energy would have been exhausted by now. However, since there are still abundant sources of useful energy (such as the sun), it is logical to conclude that the universe is finite in age. This means that there was a starting point when the universe’s energy was introduced “from the outside.” If the universe had existed throughout an actual infinite past, it would have reached an equilibrium state an infinite number of days ago, which clearly has not occurred.

- The Hawking-Penrose-Ellis Singularity Theorems: These theorems provide strong evidence for a beginning of the universe. They demonstrate that under general conditions, the universe must have originated from a singularity.

- The Borde-Guth-Vilenkin (BGV) Theorem: This theorem offers proof that the universe had a beginning. The BGV theorem implies that time itself had a starting point. Since time and space are interconnected (not only in general relativity but also in newer theories of quantum gravity), affirming a beginning of time would seem to imply a beginning to space as well, even if space started with a finite (nonzero) volume.

- Philosophical Argument on the Impossibility of Traversing an Actual Infinite: The notion of an actual infinite cannot be applied to the real world, as it leads to contradictions and defies logical comprehension. A philosophical argument for the universe’s beginning is grounded in the impossibility of traversing an actual infinite series of events.

In conclusion, the Big Bang singularity model, the BGV theorem, and general relativity collectively imply a creation event. Both philosophical and scientific evidence converge to support the notion that the universe had a definite beginning. This brings us to a compelling inquiry: Is science capable of deciphering the ultimate fact of existence, or does it, by its very nature, presuppose the existence it endeavours to comprehend?

When scientists propose that mathematical models can explain the universe’s existence, they are not engaging in groundbreaking physics but rather naively adopting the ancient Greco-Pagan philosophy of Plato. Plato, like Pythagoras, believed that since numbers and mathematics efficiently dealt with quantities, they must hold the key to explaining the universe’s existence.

At first glance, the inductive argument appears logical. If the effects of things can be mathematically quantified, the ultimate cause must be the mathematical quantities themselves. However, mathematical descriptions exist only in the minds of physicists, where they have no power to generate anything in the natural world external to our minds, let alone the whole universe. Mathematical descriptions are not causes. Believing that mathematics can cause something is akin to thinking arithmetic will increase one’s bank account. Furthermore, we have no experience of mathematics existing apart from our minds. Since all mathematics consists of information-rich expressions implying prior mental activity, any explanation invoking mathematical ideas and objects preexisting the universe implies a transcendent mental source.

Science explains one aspect of the universe by appealing to another aspect of the universe, often connecting the two by subsuming them under a natural law. For example, we explain water formation by appealing to hydrogen and oxygen’s chemical properties and an energy-releasing event causing the two to combine according to their properties. In all cases of scientific explanation, a universe must already exist, along with initial conditions, laws of nature, and so on, to have something to which they can apply. Claiming that the laws of nature alone can explain the existence of everything is a fundamental misunderstanding. Laws don’t cause things; they describe how things in nature typically proceed free of outside interference. They assume nature has certain properties. Scientific explanations presuppose the universe to be employed in the first place. Consequently, a scientific explanation cannot explain the very thing (the universe) that must exist before scientific explanations can get off the ground.

The late Stephen Hawking commented, “the actual point of creation lies outside the scope of the presently known laws of physics,” leading Alan Guth to conclude that “the instant of creation remains unexplained.” Nobel Prize winner Charles H. Townes stated, “the question of origin seems always left unanswered if we explore from a scientific view alone. Thus, I believe there is a need for some religious or metaphysical explanation.” I concur. Scientific explanations apply to ongoing temporal states or changes of states of various things according to the relevant laws. The moving of continents, the formation of the solar system, the evolution (or devolution) of life, and the decay of uranium into lead are all events or changes of state explained by other events and laws that connect them. These processes are all marked by time. They are transitions. I think it would be more fitting to suggest that science is primarily equipped to address transitions from one state to another; the act of coming into existence, however, is not a transition but rather an instantaneous event. Consequently, it seems that science may not be capable, in principle, of explaining the universe’s emergence into existence.

I am led to believe that science will never be able to explain the first event (the beginning of the universe) because doing so would require appealing to a prior event and a law connecting them. In this case, the origin of the universe would no longer be the first event; the prior explanatory event would be. But to explain the first event, one would need to postulate another prior event, resulting in a constant regression, and we would still fail to ultimately explain everything.

Proposition 3: Science cannot explain what it means to be human

Can the natural sciences truly illuminate the nature of human consciousness and the essence of being human? As conscious beings, we each possess a unique perspective of the world, shaping our individual experiences. However, scientific accounts strive to describe objects and their deterministic causes from an impartial standpoint. As a result, the subject remains unobservable by natural science, not because it resides in a separate realm, but because science operates within the conscious mind. Hence, the scientific method cannot transcend the mind to objectively observe consciousness.

Consider an alien from a distant planet, seeking to understand the nature of a human being, who stumbles upon a book on biochemistry. The most plausible hypothesis for the alien might be that a human is a physical body composed of parts, including concentrations of sodium, potassium, water, and so forth. The human being would then be perceived as a product of complex interwoven physical processes. While each description is factually accurate, the overall account falls short in addressing the question of what it means to be human. Science claims to be a comprehensive description of human nature, yet it merely provides a summary of the physical components.

The issue here is not that the account is incorrect, but rather that it seems to be an incomplete answer. If the alien were to respond to the question of what it means to be human based solely on a physical foundation, it would face challenges at every level. Each of these challenges would demand new and potentially untestable hypotheses to account for the emergence of hopes, dreams, motives, passions, concerns, and beliefs from a chemical mixture. Moreover, the resulting analysis would not identify any specific life, nor any life that has existed or will ever exist.

In the end, the alien might possess an algorithm—a coding device that enables the translation of a particular hope, desire, or belief into a set of chemical events. However, this translation would be meaningless on its own. To hold any significance, the chemical record would need to be connected to the experienced or reported hopes, desires, and beliefs of the individual. Importantly, even if we assume that the psychological, moral, and aesthetic dimensions of life align with data at the biogenetic and microphysiological levels, an unbridgeable gap remains between the seemingly meaningless occurrences at the atomic and molecular level and the phenomenologically rich domain of mental life.

The natural sciences, though invaluable in understanding the objective world, may fall short in capturing the complexities of human consciousness and the essence of being human. To grasp human experience, we must delve into concepts beyond the scientific method because the scientific approach primarily focuses on objective, measurable, and quantifiable phenomena. Human experience, however, is inherently subjective, encompassing a wide range of complex and nuanced aspects, such as emotions, beliefs, desires, and self-awareness. These aspects often defy simple quantification or measurement, and their understanding requires an interdisciplinary approach, incorporating insights from fields like psychology, philosophy, sociology, and the arts. By exploring these concepts beyond the scientific method, we can gain a more holistic and in-depth understanding of the human experience, which is essential to fully appreciate the richness of our existence.

Scientism may find a comfortable home within the realm of natural sciences, but it struggles to take root in the social sciences, and this is not without good reason. The natural sciences inherently exclude the world of qualia or subjective experiences. Concepts such as playfulness, wonder, melody, duty, and freedom play organising roles in our conscious experiences, shaping our understanding of the world in ways that no natural science can truly grasp. While science can reveal much about the ordered sequences of vibrating air, it cannot capture the essence of melodies. A melody is not merely an acoustical object; rather, it is a musical one, existing within the purely mental realm. Consequently, musical objects are sounds as perceived by self-conscious beings, defined by concepts that have no place in the science of acoustics.

The concept of a person is analogous to the concept of a melody. It influences our perception and interaction with one another but does not “carry over” into the science of our being. Science sees us as objects rather than subjects, and its descriptions of our actions fail to capture our inner feelings. When we refer to the soul, we are referring to the organising principle of first-person awareness: the capacity for self-attribution, self-knowledge, and intersubjective response, which makes a person’s life worthwhile. The kind to which we fundamentally belong is defined through a concept that does not feature in the science of our physical nature.

Our behaviour towards each other is mediated by our belief in freedom, selfhood, and the knowledge that I am I and you are you, and that each of us is a centre of free and responsible thought and action. These beliefs give rise to the world of interpersonal responses, and it is from the relationships established between us that our self-conception is derived. It seems to follow that we have an existential need to clarify the concepts of self, free choice, responsibility, and others, and that no amount of neuroscience will assist us in clarifying these concepts. What matters to us are not the invisible nervous systems that explain how people function, but the visible appearances that we interpret. Based on our interpretations, we construct responses that must, in turn, be interpreted by those to whom they are directed.

This is why our nature represents a distinct realm of human inquiry that cannot be replaced by natural science. Being immune to scientific appraisal does not cast serious doubt on the possibility of arriving at a plausible and even convincing answer that exists outside the scientific enterprise.

To be fair, one potential weakness in the presented argument resides in the presupposition that natural sciences inherently exclude the realm of qualia. Although it is accurate to assert that science has not yet furnished a comprehensive explanation for subjective experiences, we cannot entirely dismiss the possibility that future advances in cognitive science and neuroscience might illuminate this issue. However, relying on prospective discoveries remains speculative and necessitates a measure of faith. The future of scientific breakthroughs is uncertain, and predicting their outcomes is a precarious endeavour.

Moreover, this counterargument may underestimate the complexity of qualia and the challenges concomitant with reconciling subjective experiences with objective scientific explanations. Finally, it is important to clarify that while acknowledging the limitations of natural sciences in addressing subjective experiences or qualia, I do not categorically deny the potential for science to make progress in understanding aspects of consciousness. My intention is not to discredit the natural sciences but rather to recognise their current limitations and emphasise the necessity for a more comprehensive perspective that encompasses various disciplines to grasp the full complexity of the human experience.

Proposition 4: Science cannot explain objective moral duties

Building upon the previous discussion, the topic of ethics comes to the fore. If human life is reducible to mere physicality, falling under the domain of the natural sciences, and if we are merely particles, quarks, and the like, then from where do objective moral values and duties originate? If the entire history of the universe is a story of strictly physical things interacting according to the laws of nature to form other strictly physical things with strictly physical properties (all within the realm of natural sciences), this deterministic view of reality raises questions about the presence of intrinsic, normative value properties, whether moral or rational. Take, for example, the issue of responsibility. How can anyone be held responsible for actions that were determined at the very beginning of the universe? Logic suggests that determinism undermines the very essence of human moral responsibility. Quantum physicist Henry Stapp spells out the implications of the classical physics that reigned from the time of Newton until the twentieth century:

“This conception of man undermines the foundations of rational moral philosophy, and science is doubly culpable. It not only erodes the foundations of earlier value systems but also acts to strip man of any vision of himself and his place in the universe that could be the rational base for an elevated set of values.”

If one’s value is derived from chemical constituents, genetic perfection, abilities, or productivity, then eventually we’re all in trouble. Contrary to a materialistic view on human value, most of us live as if humans possess inherent or intrinsic value. While not everyone may explicitly profess such belief, this is how the majority of us live. The problem, however, is that it is challenging for naturalists to justify the inherent value of human life that we tend to assume when caring for the poor, needy, and disabled.

Many attempt to derive morality from an evolutionary standpoint. Evolution may help us discern whether specific actions aid or hinder our survival, but does that render those actions right or wrong? Moreover, what is it about survival or life in general that must be valued as a self-justified good in a self-referential and purposeless naturalistic world? Consider Richard Dawkins’ striking science-only response to 9/11 in his 1995 publication, River Out of Eden: A Darwinian View of Life:

“In a universe of blind physical forces and genetic replication, some people are going to get hurt, other people are going to get lucky, and you won’t find any rhyme or reason in it, nor any justice. The universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil and no good, nothing but blind, pitiless indifference… DNA neither cares nor knows. DNA just is. And we dance to its music.”

I cannot help but note that this statement completely undermines Dawkins’ sense of moral outrage expressed in the aftermath of 9/11. If there is “no purpose,” why the “call to arms”? If there is “no evil,” why was 9/11 a “time to get angry”? If “DNA neither cares nor knows,” why is Dawkins’ DNA seemingly conveying knowledge and apparent concern as though our DNA should also “know” and “care”? Indeed, why blame the blind fundamentalism of the terrorists and not the enlightened technology of aircraft itself when, as Dawkins writes elsewhere, “Each one of us is a machine, like an airliner only much more complicated”?

Dawkins’ inability to address these fundamental questions highlights the self-defeating nature of scientism. Most people accept the existence of objective moral and rational principles. For example, if someone violates a moral principle by committing rape, they have acted immorally, disregarding another’s intrinsic value, irrespective of any opinions. Often, we don’t live as though morality is relative. If moral values are derived solely from empirical observations, they become contingent upon the specific contexts in which they are observed. In this view, universally applicable moral principles cease to exist, as morality is reduced to a set of cultural or individual preferences. This perspective is in stark contrast to the widespread belief in objective moral values that apply to all human beings, regardless of their cultural or personal backgrounds. Rape is wrong, irrespective of the context or culture.

If someone violates a rational principle, like trading a Ferrari for an old Ford, they have acted irrationally. Science cannot account for these principles, as it is descriptive rather than prescriptive. Science describes what is the case but cannot derive a moral ought from a mere description of the way things are.

In his book “The Moral Landscape,” Sam Harris asserts that science can provide a basis for objective morality. However, Harris relies on presuppositions that his worldview cannot support. Science might be able to tell you if an action may hurt someone, but it can’t explain why you shouldn’t hurt them. Harris’s system requires an objective moral standard like “wellbeing,” but offers no objective, unchanging moral authority to establish it as right. Evolution may provide practical explanations for why we consider certain behaviours moral, but a functional argument for morality is not the same as a principled one. This commits the genetic fallacy.

Goodness and virtue cannot be determined through the scientific method. Although empathy and cooperation might have evolved as adaptive traits for human socialisation, this does not automatically translate into objective moral principles. Furthermore, evolutionary explanations often emphasise group or species survival, while morality frequently involves considerations of individual rights and responsibilities that transcend mere survival.

While we know that the abandonment of traditional moral values may lead to chaos, it is not science that tells us this. Science attempts to describe what is the case, but it cannot prescribe what ought to be the case. Science can inform you that adding strychnine to someone’s drink will kill them, but it cannot tell you whether it is morally right or wrong to poison your grandmother’s tea for an early inheritance. To further illustrate: a scientist may conduct an experiment, take measurements, and draw a conclusion, but will science dictate whether they should be honest about their findings? This issue pertains to integrity, which invokes meaning and purpose.

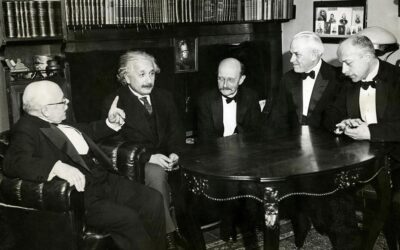

Science is grounded in the ethical principle that we ought to tell the truth and accurately report our results. However, science cannot explain why it is wrong to lie about your results. Science cannot provide itself with a moral compass or suggest which applications are best for us. As Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman bluntly stated, “ethical values lie outside the scientific realm.” In the absence of ethics, science has the potential to be perilous. Fritz Haber, who won the Nobel Prize for inventing a process to synthesise ammonia for fertilisers and feed billions, also developed explosives and poison gas for Germany during World War I. Scientific knowledge can be used for good or evil, and as Einstein once said, “You can speak of the ethical foundations of science but not of the scientific foundations of ethics.”

Philosopher and mathematician Bertrand Russell once wrote:

“While it is true that science cannot decide questions of value, that is because they cannot be intellectually decided at all, and lie outside the realm of truth and falsehood. Whatever knowledge is attainable, must be attained by scientific methods; and what science cannot discover, mankind cannot know.”

Russell acknowledges that science is unable to determine questions of value, a valid point. However, claiming that questions of value cannot be intellectually decided at all constitutes a remarkably dismissive attitude towards the significant and essential rational discipline of ethics.

Truthfulness is primarily an ethical issue rather than a scientific one, which explains why lying is generally regarded as morally wrong, not unscientific. As the act of aligning our thoughts with reality, truth is relevant to all our activities, encompassing both the intellectual and practical dimensions of science. Truth is not merely a judgement of how; it involves intention, purpose, discernment, and commitment in the act of assent. The fact that naturalism fails to offer justified reasons for moral truth does not negate its existence. If a virtuous, benevolent deity created us and defined our purpose, the moral and rational duties imposed upon us would be objectively true and real, independent of personal belief. Beyond rules and principles, the world contains intrinsically good and valuable states of affairs and things. Each individual possesses deep, inherent value, with all humans holding equal value and rights.

Natural science can say nothing of objective human value. This limitation prompted Einstein, a pivotal figure in the development of modern physics, to declare, “Science is a fine thing; religion a fine thing too.” Scientism runs the risk of reducing human beings to mere means or objects, treating them as simply another part of the material world. However, humans are more than mere objects. By exalting science while neglecting this fundamental aspect of the human condition and purpose, we risk self-abolition. Naturalists mistakenly assume that they control truth and, in the process, deny moral absolutes. That is the deadly fallout.

As a purely physical world is incompatible with the existence of objective moral values, then if objective moral values do indeed exist, this refutes naturalism, and therefore scientism. There must be more to reality. Even if someone didn’t agree that rape and murder are objectively wrong, as science presupposes truths that cannot be explained by science, naturalism can’t stand on its own, and thus, scientism falls.

Summary – Beyond Scientism: Exploring the Unquantifiable Aspects of Reality

Scientism significantly narrows our understanding of the world to only what can be described by science in terms of measurable properties. As long as there are phenomena that can be observed, measured, and quantified, science seems to offer boundless potential. However, what about the aspects of reality that cannot be measured or quantified?

Science typically does not address these non-quantitative aspects, as its primary value lies in practical applications. These applications depend on extracting measurable information used to make predictions and exert control over the physical world. In simpler terms, science focuses on what can be measured and predicted to produce useful results, often overlooking immeasurable and qualitative aspects of reality.

Scientism deviates from science when it intentionally excludes non-quantitative aspects of reality from its descriptions and irrevocably eliminates their existence altogether – claiming that there are, in fact, no non-quantitative aspects of reality.

If scientism restricts what we know to only how science describes physical phenomena, it follows that scientism also reduces what we know by confusing it with how we know. Science is an activity that describes the quantities of things, whereas scientism is the belief that those descriptions are the explanation for what actually exists; that is, the entirety of what we can know can be reduced to the level of particular entities and their elementary phenomena.

Demanding that subjects such as beauty, philosophy, theology, and morality be discarded or transformed into a framework rooted in natural science does not stem from genuine scientific inquiry. Instead, it represents the advocacy of a particular belief system, an -ism, namely scientism. Thoughtful individuals are not obligated to regard such a stance as compelling or worthy of serious consideration.

Erwin Schrödinger, a physics Nobel laureate and one of the pioneers of quantum mechanics, highlighted the limits of science:

“I am very astonished that the scientific picture of the real world is very deficient. It gives a lot of factual information, puts all our experience in a magnificently consistent order, but it is ghastly silent about all and sundry that is really near to our heart, that really matters to us. It cannot tell us a word about red and blue, bitter and sweet, physical pain and physical delight, knows nothing of beautiful and ugly, good or bad, God and eternity. Science sometimes pretends to answer questions in these domains, but the answers are very often so silly that we are not inclined to take them seriously.”

I agree. Science is wonderful and useful, but it cannot explain everything. Nobel laureate Sir Peter Medawar made a similar point in his book – Advice to a Young Scientist:

“There is no quicker way for a scientist to bring discredit upon himself and upon his profession than roundly to declare – particularly when no declaration of any kind is called for – that science knows, or soon will know, the answers to all questions worth asking, and that questions which do not admit a scientific answer are in some way non-questions or “pseudo-questions” that only simpletons ask and only the gullible profess to be able to answer.”

How did everything begin? What are we all here for? What is the point of living? Is the world divided into mind and matter, and, if so, what is mind, what is matter? Has the universe any unity or purpose? Is it evolving towards some goal? Is there a way of living that is noble and another that is base, or are all ways of living merely futile? To such questions no answers can be found in the laboratory.

Questions such as the beginning of everything, the purpose of life, the division between mind and matter, and the unity or purpose of the universe cannot be answered in the laboratory. When theists claim that there is Someone who stands as the explanation for the universe, answering why the universe was created, they are not abandoning reason, rationality, and evidence. They claim that certain questions cannot be answered by unaided reason and require another source of information – revelation from God. However, understanding and evaluating that revelation still requires reason. It was in this spirit that Francis Bacon, the father of empiricism, talked of God’s Two Books – the Book of Nature and the Bible. Reason, rationality, and evidence apply to both.

The question of why there is a universe for science to study cannot be answered by science. Nor can science answer whether there is anything behind the universe – since if there is, it will either remain unknown or must reveal itself in another manner. Stephen Hawking states:

“Traditionally these are questions for philosophy, but philosophy is dead. It has not kept up with modern developments in science, particularly in physics. As a result scientists have become the bearers of the torch of discovery in our quest for knowledge.”

This is scientism with a vengeance. Ironically, after declaring philosophy to be dead, Hawking proceeds to write a book on nothing other than the philosophy of science. Unfortunately, his scientism is philosophically illiterate. Hawking would have benefited from adopting Albert Einstein’s attitude towards philosophy in general and epistemology (the theory of knowledge – how we get to know things) in particular. Einstein wrote:

“The reciprocal relationship of epistemology and science is of noteworthy kind. They are dependent upon each other. Epistemology without contact with science becomes an empty scheme. Science without epistemology is – in so far as it is thinkable at all – primitive and muddled.”

And elsewhere he wrote: “It has often been said, and certainly not without justification, that the man of science is a poor philosopher.”

In summary, science serves as a vital instrument for comprehending the measurable dimensions of our reality. However, the adoption of scientism as a worldview leads to a reductionist approach that overlooks the significance of non-quantifiable aspects of existence. It is imperative to acknowledge the boundaries of scientific inquiry and to appreciate the contributions of philosophy, theology, and other disciplines in addressing complex questions that lie beyond the purview of science. By fostering a more nuanced understanding of the world, we can cultivate a richer intellectual landscape that transcends the limitations of scientism.

Scientism vs. Science: Defending the Integrity of Diverse Inquiry

I wish to clarify that my intention is not to undermine the value of science. Instead, I advocate for an inclusive approach that embraces the complementary roles of “science and” – science and the humanities; science and theology; science and philosophy; science and art. Those who confine reason to science alone are like toddlers who are terrified of stepping outside the confines of the nursery into the garden, preferring to play inside where it’s safe and familiar. This mindset closely parallels that of religious zealots who, despite centuries of well-documented scientific discoveries, dismiss the existence of dinosaurs based on their interpretation of sacred texts. They are shutting down the academic arena to a size they are comfortable with, to match their severely impoverished way of thinking. Why not welcome a world of knowledge that is far grander and more wondrous than the physical sciences alone can offer?

It is crucial to remember that critiquing scientism does not equate to criticising science. Reductive materialists have sought to evade metaphysics throughout history; however, reductive materialism inherently constitutes a metaphysical stance. Scientism maintains a metaphysical commitment to naturalism, either reductive or emergent materialism, and strives to frame science in a manner that aligns with this specific metaphysics. Scientism poses questions and accepts answers solely within the context of this pre-established metaphysical viewpoint. Consequently, a scientist’s research, influenced by scientism, can only yield results that reinforce the same metaphysical commitment from which it originated, as the metaphysics’ validity cannot be assessed scientifically. This strategy is, however, not science.

So scientism itself does no good service to science qua science. Rather, it attempts to hijack science to support naturalistic metaphysical commitments in which science owes no particular debt. Science does not require that naturalist, materialist metaphysics be true in order to proceed in its project of gathering and reporting empirical findings. Over the centuries, thinkers committed to materialist metaphysics have endeavoured to subsume science within their own worldview. To resist this unwarranted encroachment is to champion the integrity of science itself.

The religion and science conversation

Given the naturalist’s exclusion of God and scientism’s attempt to restrict knowledge within the domain of naturalism, it is worthwhile to explore the interaction between science and religion, albeit briefly.

The relationship between science and religion has been complex, varied, and often cooperative throughout history. Presently, science is commonly portrayed as being in conflict with religion, a notion I wholeheartedly disagree with. It is crucial to define what “conflict” entails in this context. Undeniably, scientific and theological opinions sometimes clash, presenting seemingly discordant or divergent claims. However, this type of conflict, characterised by a diversity of opinions and claims, exists within science itself as well as within religion and theology. In fact, without disagreement, little intellectual progress could be made. Hence, such conflicts should not be considered problematic. I contend that it is more accurate to speak of a conflict between scientism and religion, rather than a broad, ill-defined conflict between science and religion. Allow me to elaborate.

Modern science has undoubtedly been highly successful in answering numerous questions about the natural world. The actual contention does not revolve around whether science has something to offer, but around the claim made by scientism that nothing else does. It is these claims that render scientism a subject for critique. Religion asserts that it has significant insights into the human condition and our place in the natural world, offering a unique and valuable perspective on the truth. Conflicts arise when scientism claims that only science can explain or address the human condition. As such, it is the interaction between scientism and religion that merits our attention.

What should be our response when interpretations of scientific work conflict with interpretations of theology? Firstly, it is vital to underscore that science and theology operate from distinct perspectives and, for the most part, concentrate on divergent aspects of our understanding. Science seeks to explain the workings of the physical world and the universe through empirical observation and systematic experimentation. Theology, on the other hand, grapples with existential questions about meaning, purpose, morality, and the nature of the divine, employing a spectrum of methods including philosophical reasoning, interpretation of sacred texts, and spiritual introspection. While there can be areas of overlap, these two domains fundamentally engage with different dimensions of human knowledge and experience.

Where there can be overlap, I believe that the dominant paradigm in science-and-theology discourse is inherently biased, ensuring that science always prevails. Scientism can be defined in multiple ways: it can be seen as reductionist, simplifying the complexity of the cosmos and human life to what can be measured and arbitrated by the natural sciences, or as the result of science overstepping its jurisdiction of authority. In other words, science becomes scientism when it overreaches its purview; when, for example, it makes metaphysical pronouncements about naturalism that could never be rooted to empirical data, or when it extrapolates from the material conditions of human consciousness as if those were the only conditions for consciousness – as if biology or neuroscience, for example, are able to canvas all aspects of human consciousness.

Based on this understanding, I argue that scientism is both reductionist and overreaching. Scientism emerges when we forget that the pursuit of science is a human, cultural activity, much like other cultural activities that cannot be accounted for by the natural sciences. I posit that scientism is the result of a narrative that a secular culture wants to tell about science. Science, as a product of human creation, is an example of culture; without humans, science would not exist. Acknowledging science as culture allows for a more level playing field in the theology/science dialogue. While theological claims should be challenged and critiqued, they should not be forced to bow down to science. It is essential to recognise the distinction between science and nature, a distinction often blurred. Science is not merely a transparent magnifying glass that delivers nature “as it really is.” Rather, science is a cultural institution that focuses on nature, aims to describe it, and exposes itself to nature’s feedback through rigorous experimentation and observation. However, this does not make science “natural.” It remains a cultural layer of human creation.

In light of this, theology should not feel the need to defer to science as if it were subjecting itself to nature or reality. We should cease viewing “science” as a static body of findings and instead recognise it as a dynamic process of discovery. The history of science reveals a fallible enterprise where past ways of understanding nature give way to newer, more potent perspectives. Some philosophers of science refer to a “pessimistic induction,” pointing out the consistent failure of scientific theories to withstand the test of time, which implies that no scientific theory should be held in absolute esteem. For instance, Newton’s laws of motion, which were once believed to precisely describe the workings of nature, have since been superseded. Einstein’s theories followed, then quantum mechanics. In light of this, I have no confidence that we have reached the zenith of scientific understanding or that the science of tomorrow will mirror that of today.

Excessive dogmatism is the death knell of science, and pride, whether wielded by a scientist or a priest, is equally damaging. Accepting the fallibility of science, recognising it as a constantly evolving human enterprise, and understanding its perpetual need for correction, allows us to debunk certain grandiose claims about science. Recognising science as a dynamic process rather than a static body of facts can pave the way for a more engaging and constructive dialogue between science and theology.

Therefore, acknowledging that science is not merely a collection of immutable facts, but a dynamic, human-driven process of discovery, we can create a more balanced and enriching dialogue between science and theology. By recognising this, we allow space for theology to critically engage with science without feeling the need to bow to its claims, and we keep open the possibility that science, too, can learn from theology. This understanding transforms the interaction from a battle of superiority to a fertile ground for enriching and transformative dialogue.

The ‘How’ and the ‘Why’: Reevaluating the Roles of Science and Theology

As we delve deeper into the dialogue between science and theology, it is paramount to delineate the distinct roles these two fields play in our quest for understanding.

Science, in its essence, elucidates the ‘how’ of phenomena – the processes and mechanisms that are observable and quantifiable. It is adept at detailing the effects of how things function, but it does not inherently address why they are in the first place, which is presupposed by the how. This is why science cannot be the only means for acquiring truth. For if truth is the correspondence of thoughts to things, and if science is only one aspect of our thoughts regarding how things are (quantitatively), then science is only one means among many contributing to the process of truth acquisition, not the end-goal of truth itself. Truth and science are categorically different.

Perhaps an illustration will help explain. If I asked, why is the water boiling? You could answer that the heat from the Bunsen burner flame is being conducted through the copper base of the kettle which is agitating the molecules which are moving faster and faster, so that’s why it’s boiling. True, but actually it’s boiling because my wife wants a cup of tea. Notice that I have offered the “how” description of process before answering the question with a “why” explanation of purpose. Clearly, the how and why are not contradictory; they are complementary. There is no rational objection to the fact that we can fully describe the process of a boiling kettle and yet at the same time provide a nondescript explanation in terms of purpose. The issue is not degrees of understanding but kinds of understanding. Explaining how something happened increases our knowledge, whereas explaining why someone did it helps us understand them.

Scientism conflates science with truth, obscuring the ‘why’ of purpose by focusing solely on the ‘how’ of process. This approach is misguided. In emphasising the importance of considering “why” explanations I’m not claiming that everything happens for a personal reason, but when one is present it makes the event far more significant. The ‘why’ explanation carries with it the fundamental dimension of human agency assumed by the ‘how’ description of mathematical principles.

Diligent inquiry and progress in comprehending the ‘how’ and ‘why’ of reality have been fundamental to human advancement. Science has played a pivotal role in the evolution of medicine, sustained growth, and technological innovation. In contrast, religion offers a justification for objective moral duties and the intrinsic value of life. Science addresses the ‘what’ and ‘how’—elucidating the workings of the universe, the development of life, and so forth. It delves into the intricacies of physical reality. Religion, on the other hand, explores the ‘why’—the question of agency. Why does the universe exist? Is there an underlying purpose? Are humans inherently valuable or are we merely a conglomeration of particles? Is there an ethically and objectively correct standard for life, or are all ways of living simply matters of debatable opinion? Does a fixed and imutable point of reference exist for the definition of love, and is there anything beyond current group consensus compelling us to adhere to it? Religion wrestles with spiritual reality, encompassing meaning and responsibility.

The ‘what’ and the ‘why’ are two very distinct questions.

You can be a dedicated scientist at the highest level while simultaneously acknowledging that science cannot address every type of question about reality, including the most profound inquiries humans pose. Scientific knowledge does not instruct us on what to do or who to be. Everything crucial in guiding life falls outside the realm of science. Can any scientific discipline or method teach you how to become a truly virtuous person? Can the scientific method reveal the inherent value of a disabled child? Can the scientific method explain the beauty of ecstatic love, the kind that emerges from within, extends towards others, and willingly sacrifices for those to whom it owes no particular obligation? Science remains silent on questions that defy quantification. This is where we need to look to something higher than the scientific process. Religion, at its best, adds invaluable wisdom to scientific knowledge.

Science constitutes only a fraction of the much vaster fields of knowledge, and it would be presumptuous to dismiss or reduce all inquiries and subjects beyond the study of the physical world. Rejecting such potential knowledge would be a mistake. Seeking other sources of truth alongside science does not mean abandoning reason, rationality, or evidence. Some questions simply fall outside the purview of what science can answer, necessitating another source of information—perhaps a revelation from God. The Bible is not primarily a book of scientific processes, just as science cannot provide us with a theory on the meaning of life.

Both science and theology can and should be pursued in tandem, without either side undermining the other. For instance, the atheist often overlooks that understanding how something functions does not negate the existence of a creative intelligence behind the process. Scientific advancements have taught us new aspects of how the universe operates, but they do not inform us if there is a ‘who’ behind the ‘how.’ If I provided a comprehensive scientific explanation of how Microsoft Office works, it would not prove that Bill Gates doesn’t exist. The ‘how’ question (a question of mechanism) does not address the ‘who’ question (a question of agency), nor does it answer the ‘why’ question (a question of purpose): Why was Microsoft Office created? We can only obtain that answer if Bill Gates shares it with us; if the creator chooses to reveal it.

For example, if we were asked to explain a car, should we mention the inventor or dismiss any personal agency and assert that the car arises naturally from physical laws? Or, consider this amusing example: science can explain the physical properties of a cake and the chemical reactions involved in its baking, but a description of the physical process doesn’t touch on the fact that it was made by my grandmother for my birthday. There are different causes and levels of explanation. What we are discussing here has been familiar since the time of Aristotle, who distinguished between what he called four causes: the material cause (the material from which the cake is made); the formal cause (the form into which the materials are shaped); the efficient cause (the work of your grandmother, the baker); and the final cause (the purpose for which the cake was made – your birthday). It is the fourth of Aristotle’s causes, the final cause, which is outside the scope of natural science.

Undoubtedly, both levels of explanation—the scientific account of ‘how’ and the personal agency addressing ‘why’—are essential for a comprehensive understanding. To ask us to choose between God (personal agency) and physics (physical law) is not only a category confusion but also an oversimplification of the complex tapestry of existence. These explanations do not stand in opposition; rather, they harmoniously complement each other, enriching our grasp of reality. As Lennox said:

“When Sir Isaac Newton discovered the law of gravitation he did not say, ‘Now I have understood gravity, I don’t need God.’ In fact, Newton wrote in the Principia Mathematica, the most famous book in the history of science, that it would ‘persuade the thinking man’ to believe in God.”

In his best-selling book “A Brief History of Time,” Stephen Hawking delves into the “what” and “how” of our universe. He concludes his exploration by stating, “now if we only understood why, we would have the mind of God.” The underlying implication is that the answer to this ultimate question would need to come from a mind that transcends our material universe, suggesting a realm of understanding beyond the confines of science alone.

Science offers us the components of existence, shedding light on the “what” of our world. However, it is the “why” that binds our lives with meaning and provides a broader understanding of our purpose for being here. The search for purpose defines, drives, and explains our raison d’être. Only when we grasp the “why” can the “what” be truly comprehended.

Religion plays a vital role in addressing the “why,” thereby complementing the endeavours of science. Framing science and religion as competing forces tarnishes and weakens two potent and essential elements that should collaboratively contribute to the public good. Recognising their complementary nature allows us to appreciate the unique insights each brings to our understanding of the world and our place within it.

It is scientism, not science, that stubbornly refuses to accept any explanatory account not grounded in the material and natural laws. The insistence on this type of explanation comes from orthodoxy rather than from experience or the tenets of science itself. Scientism has functioned as a sort of fundamentalism to many. When properly understood, much of the supposed conflict between science and religion is mostly myth. And the myth is kept alive and promulgated. Before the late nineteenth century there were no two distinct camps of scientists and religionists; before that time – including the scientific revolution, there was a single intellectual enterprise, pursued by people who were mostly religious while engaged in scientific investigation. It is scientism, not science, that fuels the tension.